Before freelancing for DC Comics, Mike tried to sell this syndicated

strip idea, The Savage Empire, which was later modified to become Warlord.

Here's a Sunday sample. ©2000 Mike Grell.

Before freelancing for DC Comics, Mike tried to sell this syndicated

strip idea, The Savage Empire, which was later modified to become Warlord.

Here's a Sunday sample. ©2000 Mike Grell.

Mike Grell, Freelance

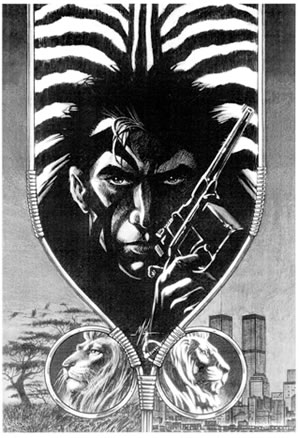

Jon Sable's creator on his days of independence

Conducted by Jon B. Cooke

Transcribed by Jon B. Knutson

From Comic

Book Artist #8

Mike Grell arrived almost stealthlike onto the comics scene in

the early '70s, and after working on numerous DC super-hero strips,

the artist established a long-standing niche as creator/writer/artist

of Warlord. Though often critically unheralded, Mike went on to become

a top-selling force in the direct sales market, notably with Jon Sable,

his trademark character he is currently developing into novel form,

and with the controversial Green Arrow: The Longbow Hunters mini-series

for DC. Mike was interviewed via phone on February 4, 2000, and the

artist copyedited the final transcript.

COMIC BOOK ARTIST: Did you have an early interest in comic

books?

MIKE GRELL: I had an early interest in just about everything

to do with comics or comic strips. My brothers and I used to buy comic

books and swap them with the neighbors, usually a hot copy of Sub-Mariner

or Captain America for a copy of Donald Duck or something like that.

Interestingly enough, it probably provided our first interest in comics.

I remember reading The Human Torch back in the days when it was The

Human Torch and Toro, and that might've been a leftover from

the Golden Age.

CBA: Did you start picking up the pen at an early age?

MIKE: Oh, yes. I grew up in an area where we didn't have

television until I was about eight years old, and I was 11 before

we got a TV set, so I grew up with radio and comic books and comic

strips, and actually learning to read books without pictures, too.

My mother was a very good artist, and she always encouraged us to

draw. Whenever a new movie would come out, my brothers and I would

sit down and draw various scenes from the movie, and I suppose that's

part of where that got started.

CBA: At an early age, did you start considering that art might

be a future for you?

MIKE: Actually, at an early age, I wanted to be a lumberjack,

just like my old man--just like the song says. [laughter] God bless

him, one year when I was 16, he got me a job working in the woods,

and I discovered how hard the old boy'd been working all these

years. There had to be a better way of making a living! [laughter]

I looked around, and my actual first thought was that I really wanted

to be the next Frank Lloyd Wright. Unfortunately for me—or possibly

fortunately for the rest of the world—I couldn't handle

the math, and it was in the days long before computers or even calculators,

so I never had any electronic help with it. I rapidly had to give

that up, and decided on a career in commercial art. I went to the

University of Wisconsin for about a year, dropped out and was going

to switch to a private art school so I could get more direct training,

and got caught up in the big draft, and faced the choice of either

being drafted in the Army or enlisting in one of the other services.

I decided four years in the Air Force was better than two years in

a foxhole, and enlisted in the Air Force in 1967. While I was in basic

training, I met a fellow by the name of Bailey Phelps—wherever

he is today—I hope he's a cartoonist, so he knows how far

of the mark he was. He told me I should forget about commercial art

and become a cartoonist instead, because according to him, cartoonists

only worked two to three days a week and earned a million dollars

a year. [laughter] Apparently, he was talking about Charles Schulz,

but I didn't realize it, I thought it was a generic thing for

cartoonists in general. A while back, I did some quick math and decided

that somebody owed me... let's see, 25 years in the business,

they owe me about $25.5 million, and about 24 years vacation.

Preliminary pencil design for Mike's Sable novel. ©2000 Mike Grell.

Preliminary pencil design for Mike's Sable novel. ©2000 Mike Grell.

CBA: [laughs] I always thought the syndicated life was the

life to have, but I've learned through interviews that it's

not necessarily what it's cracked up to be. You had an opportunity

to work on the Tarzan strip in the early '80s. Was it grueling

work?

MIKE: It was an absolute kick in the pants! It was the most

fun I've ever had as a cartoonist. I found it to be so enjoyable

and so exciting. When I was doing the color guide for my first Sunday

strip, I started to hyperventilate, and laughed so hard, I had to

go lie down. I was so excited, so thrilled by it, it was the answer

to my dream, really. Of course, over the years, I switched my focus

from the bigfoot style cartooning, the humorous stuff, to a more realistic

illustration. As far as I was concerned, that was definitely the most

fun I've had. Unfortunately, the financial rewards weren't

there, I was earning about as much in 1982 and '83 as Hogarth

was making 30 years before.

CBA: When did you get out of the service?

MIKE: In 1971, I took my discharge and went to Chicago to go

to school at the Chicago Academy of Fine Art, where I studied under

an old fellow by the name of Art Huhta. Art was one of the animators

who worked on Fantasia, in the dinosaur scene. Art was a vast body

of knowledge. While I was going to school there, I was also working

a couple of moonlight jobs, commercial art, one at an art studio doing

illustration, and another for a printer, doing paste-up and flyers

and stuff like that, little flyers. After a couple of years, both

of them offered me full-time jobs. The paste-up job was paying about

four times what the illustration job paid, but I took the illustration

job, because I was learning more.

CBA: Did you start a family?

MIKE: No, I don't have any kids of my own. I am married

now, and my third wife has presented me with a bouncing baby 17-year-old

son! [laughter] Ready-made! Mostly grown! Lauri and I have been best

friends for a long, long time. We've been together as a couple

since 1993. We've been married three-and-a-half years.

CBA: Did you start looking at comics again? Was there a point

that you left comics behind, and then...?

MIKE: Yeah, I left comics behind at about the same time I got

involved heavily in girls, at about puberty. It was pretty much normal,

back then when I was a kid, that when you got into early high school

years, you sort of stopped reading comics, although I was still involved

enough to have had Spider-Man #1, Fantastic Four, all that other stuff,

the great Marvel revolution. The New Age of DC was actually coming

back, and things like that. Then I turned my back on comics for quite

a while. Then, while I was in Saigon, I ran into a fellow who was

quite a comics collector, and he brought a few of his favorites along

with him! Among those was Green Lantern/Green Arrow, by Denny O'Neil

and illustrated by Neal Adams and Dick Giordano. It was eye-opening,

I didn't realize that people were actually writing stories about

the real world, with characters who were believable. I always thought

the Green Arrow character was more interesting, because he had no

special super-powers or anything like that, just his skill and his

personal drive and determination, philosophical outlook on the world,

that allowed him to do what he did. And right then and there I knew

that was the kind of art I wanted to do. I had my eye on comic strips,

and I worked towards that end. I took the Famous Artists' School's

correspondence course in cartooning while I was in Saigon, and it

was actually an extremely good course! It was written by guys like

Milton Caniff and Rube Goldberg... One of my other friends who

took this course 10 or 15 years before I did still had all of his

old, graded lessons, and they were graded by Norman Rockwell, who

would actually sit down and put a overlay over the work, and draw

or paint over the top of his work and send it back to him.

CBA: I think that was a lucrative deal for those guys, too.

It worked out quite successfully, I believe.

MIKE: It certainly worked out for me. When I got back to Chicago,

I discovered it was extremely difficult to sell a comic strip having

anything to do with action-adventure or continuity; everyone was interested

in the next Peanuts. Gag strips were the way everything was going,

and when I walked into the Chicago Tribune one day and presented my

portfolio, the editor looked at me, shook his head, and said, "If

you'd been here 15 years ago, you'd have had it made."

What he did do was steer me towards Dale Messick, who was doing, of

course, the Brenda Starr strip. She was in need of another assistant

to take some of the workload off her, and so I went and showed her

my portfolio, and went to work immediately. I used to do just about

everything with the exception of the layouts; she had another assistant

who did the layouts and the lettering, sort of blocking in future

positions and things like that. I'd take those layouts and tighten

them up, and draw in ink everything except Brenda's face, and

Dale would do Brenda's face after that. When I write my autobiography,

finally, I'm going to entitle it, Doing Brenda's Body. [laughter]

CBA: Or a movie, for that matter. [laughs]

MIKE: I figure I've got a million-seller on the title

alone!

CBA: What's the genesis of The Savage Empire?

MIKE: The Savage Empire was the comic strip I had drawn prior

to going out to New York in 1973. They were my samples; I was trying

to sell this fantasy comic strip in New York, and I thought the ideal

spot to do that would be at the New York Comic Convention. I figured

it would be swarming with people from all different walks of life

in the comics industry, including comic strip editors... I didn't

see how they could possibly turn me down. After New York, I discovered

that not only were they not interested in adventure strips, I couldn't

even get in the door. Fortunately for me, at the New York Comic Con

in '73, I met Irv Novick and Allan Asherman. Allan was working

for Joe Kubert at the time. They both took a look at my portfolio,

and Irv told me in no uncertain terms I should get my carcass up to

Julie Schwartz's office and show him my stuff. I was unable to

do it on that trip, but I came back and marched into Julie's

office with my portfolio in hand, and started my prepared encyclopedia

salesman's speech, "Good afternoon, Mr. Schwartz, can I

interest you in this deluxe 37-volume set of encyclopedias?"(If

you get interrupted anywhere along the line, you have to go all the

way back to, "Good afternoon, Mr. Schwartz.") [laughter]

I got exactly as far as, "Good Afternoon, Mr. Schwartz,"

and he said, "What the hell makes you think you can draw comics?"

[laughter] I unzipped my portfolio and dropped it on his desk, and

I said, "Take a look, and you tell me." He flipped through

the pages, and he called Joe Orlando in from next door, and I walked

out half an hour later with a script in my hand. Joe managed to see

something in those early drawings that led him to believe I was worth

taking a shot on. He gave me the script to draw a back-up comic for

"Aquaman."

CBA: Is there a relationship between The Savage Empire and

Warlord?

MIKE: Absolutely. After spending some time at DC, I still had

this desire to do that story, and I found out there was another comic

book company starting up, Atlas/Seaboard, and they were reportedly

offering a rather munificent sum per page. (In fact, it was easily

double what DC was paying at the time.) I wanted to cash in on that,

but also didn't want to jeopardize my position at DC working

on the books I had. I went over, spoke to the editor, and pitched

them on The Savage Empire, and they liked it quite a lot. I said basically,

what I wanted to do was keep this under our hats until I had the book

handed in; I wanted to be able to demonstrate that I could still keep

my commitment to DC at the same time. That lasted about the amount

of time it took me to walk from Atlas' office to DC—Carmine

had very quickly found out about it. He met me in the hallway, and

explained he'd spoken with the editor over at Atlas, and had

been informed they had me tied up for two books a month, and wanted

to know why I hadn't come to him with this in the first place.

I said, "DC doesn't really have a great track record for

the fantasy type stuff, and I didn't think you'd be interested."

He said, "Let me be the judge of that." So I followed him

down the hall to his office, walked in and he had to take a call while

I was sitting there. And in that brief period of time, I realized

he wasn't going to buy it. There was something wrong with The

Savage Empire as it stood, it just wasn't going to fly. So, in

that minute-and-a-half he was talking to whomever on the telephone,

I revamped and revised the story in my head and extemporized a pitch

to him. And he bought it!

CBA: On the fly, Mike, eh?

MIKE: He bought it. He said "Run it past Joe Orlando,

and if Joe likes it, it's cleared."

CBA: Do you remember what kind of changes you made?

MIKE: Oh, yeah. Basically, the original concept of The Savage

Empire was the hero, an archaeologist named Jason Cord, stumbles on

a time portal that transported him back to Atlantis. While there,

he's sort of the catalyst for all the advanced development...

and disasters that occur in Atlantis.

CBA: The time-travel thing.

MIKE: Yeah, the changes I made, of course, were transporting

him to a land at the center of the Earth, a combination of... oh,

lord, a lot of things, from Jules Verne to Edgar Rice Burroughs'

Pellucidar. There was a book written called The Smoky God, and there

were stories about Admiral Byrd's expedition and having found

a land mass somewhere beyond the North Pole and speculation that there

was a world at the center of the Earth. So I put that all together,

kept a few of the characters the same—the character Deimos is

the same—and changed the... actually, the character relationships

are pretty much the same. A good deal of plot direction is similar.

Basically, I made it an Air Force pilot, drawing on some of my own

knowledge and background, brushed up the character and made him a

little bit more three-dimensional, and there it was.

CBA: Backtracking a little bit, your first job was an Aquaman

story in Adventure Comics. Was there any reaction to when you delivered

the job?

MIKE: Yeah, as a matter of fact, Joe Orlando took one look

at the first page and shook his head and said, "You can't

do this anymore." I said, "What anymore?" He said,

"You've got Aquaman mooning the reader."

CBA: Oh, I remember that now! The swimming?

MIKE: Right. It never dawned on me. I'd done another panel

of Aquaman sitting on the throne, and it made it look like he was

sitting on a toilet. [laughter] Between Joe and Julie, I became known

as the guy who drew Aquaman on the toilet. Joe became my mentor. When

I would bring an issue in-house, and he spotted an error in drawing,

he'd sit down and give me a drawing lesson on the spot, show

me where I'd made mistakes, and help with a lot of corrections.

CBA: So Joe was your first editor at DC, and then Murray Boltinoff?

MIKE: Then Murray Boltinoff. I'd just turned in my first

Aquaman job, and picked up another story from Joe, and Murray was

on vacation. He came back and discovered he was minus an artist; Dave

Cockrum and I had sort of passed each other in the hallway, him walking

out as I was walking in. Joe Orlando called me up and said, "There's

something coming up, and I was wondering if you'd mind if I put

your name up for it." Mind? Lord, it would be a steady gig! I

needed the work, so I said, "Absolutely, I want it." Murray

started me inking over Dave on one story, and I took over from then.

CBA: Did you have any conversation with Dave, that he left

in anger?

MIKE: No. Not until years later, and in fact, the only conversation

at that point was the extent of congratulating him on the hard work

he'd done, and thanking him for having created these elaborate

character sketchbooks that had served as a basic bible of how to draw

the characters. I was at a loss for some of the costumes, it was very

difficult to get them accurate. When I told him that, he just laughed

and said, "I had the same problem myself, that's why I did

the sketchbook, so I could remember them!" 26 characters and

26 costumes, a real army. The thing is, with the exception of the

doodad on the front of the Shirking Violet costume, I bet I can draw

every one of them from memory today. After two years of drawing them

every day, it tends to stick with you.

CBA: The main reason Dave quit DC at the time was because

he'd requested an exception to the rule that DC kept the art,

and he said there was a couple-page spread of a wedding scene from

"Legion" that he wanted, because he'd put so much work

into it, and he was denied getting it, so he quit in anger. Did you

ever have a problem getting your art back?

MIKE: Of course I wanted my art back. It was very interesting,

because at the outset, I was told they'd just changed the policy,

so possibly it was a reflection of Dave's move. Maybe that was

the eye-opener that made them realize they had to do it. I know Marvel

was giving the art back, or at least some of it, not necessarily all

of the stuff. There were people who were getting their art back. I

think that kind of attitude of the company keeping the art formed

very early on, and of course continued on with Mad magazine, but no

one seemed to mind because Mad always paid so much that nobody cared.

CBA: Did you find inspiration in the work of Neal Adams when

you were first starting out?

MIKE: What, am I going to lie and say no?!? [laughter] Of course,

I was inspired by Neal. He was probably the strongest individual influence

on my art, with the possible exception of Joseph Clement Coll and

Paul Calle. I went through a couple of evolutions in my art style.

(Art is a very much a growth process, and if you stop growing, and

stop changing and developing, you stagnate, and the sound you hear

is the footsteps of the next young hot-shot about to run you over.)

I really admired Neal's pencil work and the realism he put into

the characters, the feeling, the emotion that he could generate. Interestingly,

I always thought that Dick Giordano was the better inker, and that

was because of his style and technique for the medium we were working

in. Neal's line tended to be a bit fine, and at times, reproduction

in the medium didn't do it justice. Dick's was bolder, and

I like that quite a lot. Then I started doing the Tarzan comic strip,

and I went back and re-introduced myself to Burne Hogarth and Hal

Foster; Foster was my mother's favorite artist.

Mike's cover art, sans lettering, for his upcoming novel, Sable.

©2000 Mike Grell.

Mike's cover art, sans lettering, for his upcoming novel, Sable.

©2000 Mike Grell.

CBA: Did you adapt pretty quickly to comics? How many pages

could you do in a week, for example? Or any given day, what would

be your schedule?

MIKE: Back then, my output of pencils was between three and

five pages a day. If you ask me when I slept, the answer is, I didn't.

I fell back on the Frank Lloyd Wright system of cat-napping, I would

work for 20 hours straight and sleep for an hour, then I'd work

for another eight or ten hours, until I couldn't work any more,

then I'd sleep for two or three hours. Absolute minimums. I'd

get up and work some more, until I dropped. Joe Orlando's wife

had met me when I first hit town, and two months later, she took a

look at me, and said, "My God, what happened to you?" I

couldn't understand what she was referring to. I took a look

at myself in the mirror, and realized I had aged quite considerably

in that amount of time! [laughs] Almost as bad as being in the White

House. [laughter] During that time, I never turned down any work.

If someone said, "Can you do this?" the answer was always

yes. I'd take the job, because you never know when the next one's

coming. Sort of explained why, in a very short period of time, if

you look at the books from '73, '74, '75, I seem to

have done everything, been everywhere, and drawn just about every

book there was. That's not really true, but my name appeared

in a number of titles all at once.

CBA: You covered pretty much most of the major characters,

it seems to me. Batman, Deadman, Phantom Stranger...

MIKE: Well, Deadman and Phantom Stranger was a story together,

but yeah, at one time I think I've done covers at least for just

about everyone, including Superman and Batman, Wonder Woman....

I even brutalized the inking on a story Doug Wildy penciled for Our

Army At War, I think it was.

CBA: After Joe's wife said that to you, did you wake

up, so to speak, and re-adapt your schedule to not killing yourself?

MIKE: No, I was a workaholic for seven years. I can't

claim to be a workaholic any more, but there's a downside to

that as well as an upside. The upside of course being the more prolific

you are, the more rapidly your name and fame spreads. And the downside

is it's very hard on relationships and marriages.

CBA: And yours suffered?

MIKE: [laughs] Yeah, I'd say so. I was married the first

time for 13 years, and the second time for five, followed by ten years

of bachelorhood. And then I finally found my soulmate.

CBA: Cool. So, the first appearance of Warlord was in First

Issue Special, right? Was that cool with you, or did you hope they'd

start the series at number one?

MIKE: The agreement I had with Carmine Infantino was that it

would begin in First Issue Special because we were trying to show

that First Issue Special was a springboard for new features, and that

it would guarantee me a six-issue run. Of course, after about the

third issue of the book, I was surprised to find a little blurb on

the bottom saying "The End"; Carmine had canceled the book

without mentioning it to me. Fortunately for me, about a month later,

the regime at DC Comics changed, and someone canceled Carmine. Jenette

Kahn kept up on everything that was going on. She looked through the

line-up of books and said, "Where's The Warlord?" They

said, "Well, Carmine canceled it." She said, "Well,

it's uncancelled," and she immediately put it back on the

schedule. Shortly after that, there was the DC Implosion, and it went

from being a bi-monthly book to a monthly book.

CBA: So, to what do you attribute the success of Warlord?

Was it that it fell into the Conan niche of readership that transcended

comics fans per se, and you got to a male post-adolescent audience?

The book lasted for quite a long time, didn't it?

MIKE: Ah, yes it did! I have to say that far from targeting

a specific audience with that book, I wrote Warlord for me. I wrote

the story I wanted to read, and yes, I like that kind of stuff. I

like the Tarzan stuff, I like the high adventure/heroic action stuff,

and I wanted to create a format where I could do any kind of story—you

could get fantasy stories, you could get adventure stories, you could

get romance, you could get comedy—to create a format where none

of this would seem awkward or out of place, if I chose to do it. This

is one of the reasons I fought for years and years against the concept

of ever doing a map of Skartaris, because that would instantly lock

me into defining boundaries of the world that was a world of imagination,

and I thought imagination was the most important part of it. So, whatever

was "right" for the readers, it was because it was right

for me first.

CBA: It's one thing you ran counter to a lot of aspects

of fandom that were going on at the time, the strict adherence to

continuity; and yet you were blessed to have a book that wasn't

a part of continuity, that you could create your own, so to speak.

MIKE: I was very fortunate, I had Joe Orlando's backing

in that. There was a very strong cry for continuity; they wanted to

know where this fit in the niche of the DC Universe, and I said, "It

doesn't." They were upset by that because everything had

to have its place.

CBA: [laughs] Even Sugar and Spike!

MIKE: Julie Schwartz created a phrase, "Call it the Grellverse!"

[laughter] It didn't fit into the niche, so in order to explain

this, there was Earth-1, Earth-2, Earth-3, and Earth-Grell. [laughter]

CBA: That must've felt good!

MIKE: Yeah, it was great as far as I was concerned. Again,

it gave me the freedom to explore all of it, and did not bind me to

any particular continuity. I was pretty alarmed after I left the series

and found they'd almost immediately inserted DC super-heroes.

Julie had a great argument for why they couldn't possibly put

The Warlord into the standard universe, and why they had to leave

it the hell alone, and that was, very simply, in the DC continuity,

Superman had already drilled through the center of the Earth, straight

through, and if Skartaris had been there, he'd have discovered

it.

CBA: Never mind Cave Carson! [laughs] So, did your star start

to rise at DC? You had your own book, you were writing, you were drawing,

you were inking.

MIKE: Yeah, as a matter of fact. At the time I took over Legion

of Super-Heroes, sales were relatively marginal, but somewhere along

the line—I'm not claiming credit for this, by any means,

there were a number of really great writers and other people involved

with the book—but sales on that book really escalated very quickly.

For some reason, which I won't claim credit for, the book became

DC's number one selling title, and shortly after I began doing

The Warlord, The Warlord became DC's number one selling title.

CBA: So did you see a commensurate raise in page rate?

MIKE: I saw a raise in page rate, I got the same raise that

everyone else did, and I've always gotten DC's top rate

with two exceptions: Curt Swan and Murphy Anderson! I understand that

Curt Swan had something of a sweetheart deal for a time, and I don't

know how long that continued, but I may not have been getting the

same rate he was, or perhaps anywhere near it, but I never really

expected it. And I think Murphy Anderson possibly had that at the

same time, but I can't say that with any certainty. There was

one other time when Julie called me up and asked me to do a pin-up

illustration for the Superman anniversary issue, and gave me a list

of everybody who had worked on it. I knew that John Byrne's standard

was, no matter where he went, he got the top rate or he got whatever

the top guy got plus a dollar. That was perhaps a running joke, but

when Julie said that, I said, "Okay, provided I get whatever

John Byrne gets, plus a dollar!" [laughter] When the check arrived,

it was for $251! [laughter] It had an annotation, "Per agreement,

John Byrne's rate plus $1."

CBA: Did DC have to approve the story in pencil form before?

MIKE: Oh, yeah. I would always send the story in pencils first.

In fact, I never trust myself to work without an editor, I've

seen too many disasters from guys who thought they were their own

best editors.

CBA: Did many editorial changes take place working with Joe?

MIKE: There was the occasional Aquaman on the toilet...

[laughter] a few minor things, as far as storylines, working with

Joe, but overall, no. Working with Julie was another case altogether.

Julie had a particular idea of what kind of stories he wanted to tell,

and would occasionally run a bit roughshod over my stories. As a for

instance, I wrote a plot for a Green Arrow story that was being done

as a back-up, and it was actually my first attempt at writing. Elliot

Maggin was doing the scripts at that moment, and I wanted a shot at

plotting a story. I submitted the plot, and Julie said, "No,

no, no, this isn't what it is, this is what it is," and

he told me my story, changing it pretty much completely. The story

that was ultimately printed had to do with a young boy who was going

around essentially tracking down and killing Nazi war criminals using

a sling with rocks, and the young boy was actually the re-incarnation

of King David. My version had to wait until The Longbow Hunters. I

had created the character Shado, and Julie didn't like it, so

I just put it on the shelf. But nothing is ever wasted, nothing is

ever forgotten, until the time was right. Years later, when it was

time to revise and revamp Green Arrow, I pulled up that character

and updated the story a bit.

CBA: Were you involved at all in the lobbying for the revival

of Green Lantern/Green Arrow?

MIKE: I happened to be in a hallway one day when I overheard

a conversation where Denny O'Neil was talking about bringing

back Green Lantern/Green Arrow, and I walked up to him and said, "Who

do I have to kill to get this job?" He said, "Are you interested?"

I said, "Oh, yeah!" Thereby hangs fate! That as a real kick.

I learned more about storytelling from Denny O'Neil than anyone

else in the business. He's still the best storyteller there ever

was.

CBA: So, when you were doing Warlord, and you were obviously

doing pretty much a complete package for them, were you disgruntled

at all with the situation with creators, or did you have your eye

on the horizon for self-owned properties?

MIKE: Well, yeah, I was naturally disgruntled. I was disappointed

that the Atlas/Seaboard thing didn't pan out, and I thought I

had been unfairly dealt with by the editor over there. I stayed with

DC, and I always resented the idea that, no matter what you created,

it was sort of like working for IBM and inventing a new computer,

and after 20 years, getting a gold watch and a pat on the back. The

same thing happened with Walt Disney and Oswald the Rabbit. Basically,

Disney and I did the same thing: We went to where the pastures were

greener.

CBA: So, you stayed with Warlord for 50 issues?

MIKE: I was with Warlord for about 50 issues, but for a year

or so after that, my then-wife Sharon and I plotted it together, and

she would write the scripts and I'd do the covers.

CBA: What was the genesis of Starslayer?

MIKE: I got the opportunity from Pacific Comics to create a

project. I was approached by the Schanes brothers, Bill and Steve,

who had this concept for a new company that would allow people to

create and own their own characters, and thereby sharing a larger

portion of the earnings on it. You'd keep the copyright, and

things like that, and it was exactly what I was looking for. I had

Starslayer originally planned as a DC project, and it was destined

to be a direct counterpoint of Warlord; instead of a modern man in

a primitive society, I decided to go the other way around and take

a primitive man and put him into the middle of a very futuristic society,

and watch what happened there. It was actually on the schedule at

DC at the time of the Implosion, and it had been announced, but it

fell by the wayside. So Steve and Bill knew about Starslayer, and

they said, "I understand you have a project, and we'd be

very interested in having you come over and do it." I was actually

the first person to sign with them, Jack Kirby signed a couple of

weeks later. But because Jack was Jack, he'd draw half a book

while we were speaking! [laughter] He delivered his first, and it

was printed first, but I was actually the first person to sign.

CBA: Were you nervous about that? This is the first real independent

publisher.

MIKE: I wasn't the least bit nervous about it. This was

another step. I was doing the Tarzan comic strip at the time, and

The Warlord was continuing... in fact, that was sort of the point

where I decided that my energy needed to be a bit more focused, and

that was the reason I stepped back from doing the artwork and writing

the scripts. I sort of phased myself back, and had a lot more time

to devote to what I knew was the coming wave.

CBA: How long did you produce Starslayer?

MIKE: I did six issues with Pacific Comics, and then wrote

the first few issues for First, when I made the switchover. Pacific

had not succeeded in doing what they had intended, at least not very

well, I had thought, and there was some organizational difficulty,

and some other problems they just couldn't surmount. So I finished

out the run I had intended, and while I was doing that, I got a call

from Mike Gold, who was involved in a new start-up company called

First Comics. (One of my friends said, "First comics, then drugs,

then the baby-sitter winds up in the freezer...".) [laughter]

CBA: You knew Mike from DC, right?

MIKE: Yes. He wanted to know if I was interested in coming

over and doing a project for them, and oh, by the way, there was also

a spot in the line-up for Starslayer, if I wanted to bring Starslayer

over. I jumped on the chance. In fact, I was the second person to

sign with First Comics. I would've been first, except they already

had Joe Staton signed, and that was because Joe was their art director.

It was pretty much a natural thing, that he'd be first in line.

I signed on to do Sable, created the concept for Sable, and agreed

that after that, I'd stay with Starslayer and do the launch with

them, write the first few issues for them, and turn it over to the

able hands of John Ostrander.

CBA: With Starslayer, did you talk with John about the approach

to the character, or did you just let it go?

MIKE: We spoke about it, and from our early conversation, I

knew he had a lock on the character, and I just let it go. I was interested

enough in Sable, and confident enough in John that I was able to walk

away and be satisfied with what he did. Perhaps it was philosophy

that comes with age, or experience, or something, or maybe it was

just a measure of the immense admiration I had for his talent. But

I knew that what John was going to do with the character from the

point I left it off was going to be perhaps different from what I

would have done, but certainly better than any idea I had in mind

at that point. I had already taken the character where I wanted him

to go, as far as I had planned for him to go, and I was quite content

to leave him in John's care.

CBA: What's the genesis of Jon Sable?

MIKE: Jon Sable is a reflection of all the great African adventure

stories I'd read when I was a kid, and my dreams of going to

Africa and hunting big game. And I suppose a combination of all those

things plus the idea that people were—at least I was, at that

moment—tired of drawing costumed super-heroes. I was tired of

drawing muscle-bound guys in skin-tight suits, and I wanted to do

something else that would allow me to do more stories that dealt with

the real world. In order to do that, I needed a character that broke

all the rules, so I did! I took the standard concept of a comic book

character, which is basically the Bruce Wayne/Batman formula—by

day, the mild-mannered you-name-it, by night, the dark avenger—and

I reversed it! I said, "Here's the deal: Here is a guy whom

everyone knows is Mr. Blood 'N Guts, he's Mr. Action-Adventure,

go anywhere, do anything for hire," which is also breaking the

mold of the standard comic book character, this guy is doing it for

money, or at least, he says he is. I decided that his big, deep, dark

secret was that he was also a closet nice guy who wrote children's

books. Everyone who knew him in his day-to-day life knew he was Mr.

Blood & Thunder, and only a few folks knew he wrote these very

sweet children's books. I think that was probably the hook, the

thing that made Sable so unique. I fully expected that when I started

that book, I'd lose anywhere from a third to even half of my

readership, and I was wrong. I had vastly underestimated my readers,

and I discovered that at the same time I was growing and changing

and evolving in my tastes, so were they! They were looking for something

that would satisfy that changing taste, and I'm quite proud of

the fact that people used to walk up to me and say, "I don't

read comic books, but a friend of mine showed me yours, and I'm

hooked." I'd just laugh, and say, "It might have been

cheaper if they'd just bought you some cocaine." [laughter]

It's a source of no small amount of pride to me that most of

my Sable readers are older and... I won't say more intelligent,

but they have a bit more refined taste in their reading than other

people. I met Walter Koenig, of Star Trek, a number of years ago,

and he said, "One of my friends recommended your book to me,

and I really like it." I said, "Oh, who's your friend?"

He said, "Harlan Ellison." [laughter] There's a compliment

for you right there!

CBA: You had a lot of long-running books. Sable lasted for

how many issues?

MIKE: [laughs] I don't know... a lot... a bunch.

[laughs]

CBA: I'll look it up. [Jon Sable, Freelance lasted 56

issues at First Comics, from 1983-88... Then, it was Sable at First

for 27 issues, from 1988-90, and finally Mike Grell's Sable at

First lasted 10 issues in 1990, each time starting back at #1.—Jon

Knutson.]

MIKE: I probably stayed on Sable for 50-odd issues.

CBA: That was a monthly book?

MIKE: Yeah. At one point, I had to phase back and just do the

writing. At that point, I was also involved with starting up The Longbow

Hunters.

CBA: Was there financial rewards in the direct market?

MIKE: Oh, of course, of course. My annual income tripled. It

was nice to see that kind of financial payoff, but even more so, I

think it was very heartening to discover we had done something right.

CBA: Were you able to maintain an interest with Jon Sable;

did it wane at all?

MIKE: To this day, Sable is still my favorite character I've

ever created—to the extent that I've just completed my first

novel, which is going to be published in July by Tom Doherty and Associates

under their Forge imprint. I'm working on the second novel in

the series now.

CBA: Great. Are you doing the cover? [laughs]

MIKE: As a matter of fact, I did paint the cover for the novel.

CBA: So, you're bringing Jon Sable into crime fiction?

MIKE: Yeah. Action-adventure, he's still what he is and

what he was, but considerably more fleshed out. Anyone who reads the

novel will find things that are familiar, and will find things that

are different. Sable today is a reflection of my growth as well, a

certain realization that the world today is not the world it was 18

years ago, when I first created the character. Sable lives in this

world, or much of this world, and if anyone thinks they know the end

of this story because they've read the comic book, they're

in for a hell of a surprise! The story does not track the comic book

strictly. The characters are not necessarily the same, although the

characters who appear are basically the same characters, but there's

a hell of a zinger in there that, every now and then, will take them

by surprise.

CBA: When did you say that book's going to be released?

MIKE: In July. It's coming out in hardcover first.

CBA: Anything else you'd like to add?

MIKE: Gosharoonie. [laughter] Yeah, as a matter of fact, there

are a couple of things. I'd like to mention what I've been

doing and where I've been directing my energy. I made a concerted

effort a couple of years ago to spend more time writing; I'm

beginning to think that's where I have perhaps the greatest contribution

to give. If anything, I'd like to be remembered as a storyteller

and that includes not just comics, but in prose, as well. I have written

this Sable novel, and I'm at work on another story and I've

also begun the second novel in the Sable series. It's my intent

that this should be a continuing series, if I can find the readership

for it. I'm going to be doing another Sable comic project. I'm

also tackling screenwriting; I've been working recently on closing

an option for a screenplay, and hopefully, before this sees print,

you can phone me back and I can actually make an announcement. At

this point, I can't, other than to say there is motion towards,

and things are looking very positive.

(Presented here are excerpts of Mike Grell's interview. Be sure

to pick up COMIC BOOK ARTIST #8 for the full

interview!)

To make subscription and back issue orders easier for our readers (especially

those overseas), we now accept VISA and MASTERCARD on our secure

web store! ( Phone, fax,

mail and e-mail

accepted, too!)

Sign up here to receive periodic updates about what's going on in

the world of TwoMorrows Publishing.

Click here to download

our new Fall-Winter catalog (2mb PDF file)

|