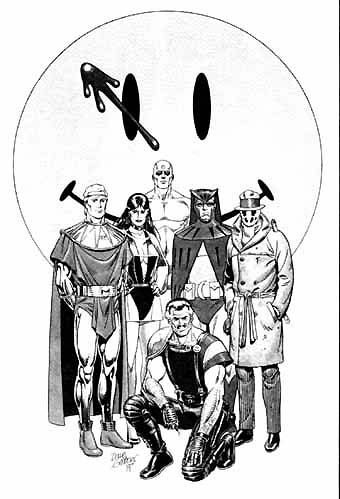

T-Shirt design by Dave Gibbons adapted from DC's Who's Who #5 featuring

the cast of Watchmen.

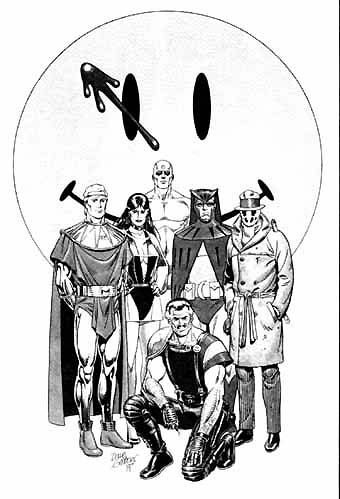

T-Shirt design by Dave Gibbons adapted from DC's Who's Who #5 featuring

the cast of Watchmen.

©2000 DC Comics.

Toasting Absent Heroes

Alan Moore discusses the Charlton-Watchmen Connection

Conducted by & © Jon B. Cooke

Transcribed by Jon B. Knutson

From Comic

Book Artist #9

To admit I felt decidedly out of place calling one of comics'

best writers to discuss—ugh! of all topics!—comic book characters

is a drastic understatement, but the sheer coolness of having a chat

with Mr. Alan Moore eased the prospect considerably. The self-professed

anarchist is plainly a nice guy and we spent more time talking about

a real-life character—Steve Ditko—than, say, the relationship

between Judomaster and Tiger. Alan currently rules the marketplace

with his critically-successful and popular America's Best Comics

line, his and Eddie Campbell's From Hell collection is flying

off bookstore shelves, and life seems pretty good for the British

writer. And, yes, good reader, there really is a connection with the

wildly-popular scribe and Charlton Comics. This interview took place

via phone on June 16, 2000. (Special thanks to JBK for the speedy

transcription.)

Comic Book Artist: Did you read Charlton comics as a kid?

Alan Moore: Yes, I did. It was kind of pecking order situation,

with the distribution of all American comics being very spotty in

England. I believe they were originally brought over as ballast on

ships, which meant there'd be sometimes a whole month of a particular

comic, or even a whole lot of comics that I just missed. So, consequently,

I'd buy my favorites early in the month, and then a little later,

I'd probably buy my second favorites [laughter]... and by the

end of the month, I'd be down to Casper, the Friendly Ghost just

to keep my comic habit fulfilled. Somewhere along the way there, I'd

see the Archie/MLJ/Mighty super-hero comics, the Tower comics that

were around at the time....

CBA: Was Charlton at the bottom of the list for you?

Alan: They'd vary, it would depend. Charlton would be

at some points low on the list, but then, there was a wonderful period

which I later realized was when Dick Giordano was having a great deal

of creative say in the Charlton books, when they became very high

on the list. There's still one of the books, Charlton Premiere—sort

of a Showcase title—and I remember in the second or third issue

of that, there was this wonderful thing called "Children of Doom"

by Pat Boyette, who died recently. It was an incredibly sort of progressive

piece of storytelling. He was obviously, I'd imagine, looking

at artists like Steranko that were coming up and messing around with

the form and sort of experimenting. Pat decided to pitch his own hat

into the ring, apparently.

Prior to that golden period when Dick was editor, I very much enjoyed

the Steve Ditko stuff—Captain Atom and the Charlton monster books—so

the main reason that I liked Charlton would've been probably

Steve Ditko, originally. Not to say that there weren't other

great artists and writers, but the ace of it all was, Ditko was the

only one that I really noticed, until that period when Dick took over.

I remember there was a very short-lived strip that I think was probably

based on Harlan Ellison's "Repent, Harlequin! Said the Tick-Tock

Man" that was about a kind of futuristic jester character drawn

by Jim Aparo. He might've even been called the Harlequin or something

like that, but I remember it was drawn by Jim Aparo, it lasted for

a couple of episodes, probably written by Steve Skeates or somebody.

There were some very good little strips, and then of course, there

was that big Charlton revamp where we got the new Blue Beetle, the

new Captain Atom, and so forth, which was a shot in the arm. All of

these things contributed in pushing Charlton higher up my league title

of which comics to buy first. They never quite ousted Marvel or DC,

but during that golden period, Charlton was up there with the best

of them.

CBA: Do you recall The Question?

Alan: Yes, I do. That was another very interesting character,

and it was almost a pure Steve Ditko character, in that it was odd-looking.

"The Question" didn't look like any other super-hero

on the market, and it also seemed to be a kind of mainstream comics

version of Steve Ditko's far more radical "Mr. A,"

from witzend. I remember at the time—this would've been

when I was just starting to get involved in British comics fandom—there

was a British fanzine that was published over here by a gentleman

called Stan Nichols (who has since gone to write a number of fantasy

books). In Stan's fanzine, Stardock, there was an article called

"Propaganda, or Why the Blue Beetle Voted for George Wallace."

[laughter] This was the late-'60s, and British comics fandom

had quite a strong hippie element. Despite the fact that Steve Ditko

was obviously a hero to the hippies with his psychedelic "Dr.

Strange" work and for the teen angst of Spider-Man, Ditko's

politics were obviously very different from those fans. His views

were apparent through his portrayals of Mr. A and the protesters or

beatniks that occasionally surfaced in his other work. I think this

article was the first to actually point out that, yes, Steve Ditko

did have a very right-wing agenda (which of course, he's completely

entitled to), but at the time, it was quite interesting, and that

probably led to me portraying [Watchmen character] Rorschach as an

extremely right-wing character.

CBA: When you read some of Ditko's diatribes in "The

Question" and in some issues of Blue Beetle, did you read it

with bemusement or disgust?

Alan: Well...

CBA: A mix of both?

Alan: Well, no. I can look at Salvador Dali's work and

marvel at it, despite the fact that I believe that Dali was probably

a completely disgusting human being [laughter] and borderline fascist,

but that doesn't detract from the genius of his artwork. With

Steve Ditko, I at least felt that though Steve Ditko's political

agenda was very different to mine, Steve Ditko had a political agenda,

and that in some ways set him above most of his contemporaries. During

the '60s, I learned pretty quickly about the sources of Steve

Ditko's ideas, and I realized very early on that he was very

fond of the writing of Ayn Rand.

CBA: Did you explore her philosophy?

Alan: I had to look at The Fountainhead. I have to say I found

Ayn Rand's philosophy laughable. It was a "white supremacist

dreams of the master race," burnt in an early-20th century form.

Her ideas didn't really appeal to me, but they seemed to be the

kind of ideas that people would espouse, people who might secretly

believe themselves to be part of the elite, and not part of the excluded

majority. I would basically disagree with all of Ditko's ideas,

but he has to be given credit for expressing these political ideas.

I believe some feminists regard Dave Sim in much the same light; they

might disagree with everything he says, but at least there is some

sort of sexual-political debate going on there. So I've got respect

for Ditko.

A few years ago, I was in a local rock band called "The Emperors

of Ice Cream, "and one of our numbers that always went down very

well live, was a thing called, "Mr. A." The beat and the

tune of it were completely stolen from "Sister Ray" by the

Velvet Underground, but the lyrics were all about Steve Ditko.

CBA: "Right/wrong, black/white"? [laughter]

Alan: One of the verses was, "He takes a card and shades

one-half of it in dark, so he can demonstrate to you just what he

means/He says, 'There's wrong and there's right, there's

black and there's white, and there is nothing, nothing in-between.'

That's what Mr. A says." [laughter] And then we'd go

into the chorus. Yeah, it was a Velvet Underground thrash, but with

lyrics about Steve Ditko, which were very sympathetic, because at

that time, I'd heard that Steve Ditko was pretty much harmless,

living at the YMCA or something like that. This was, I think, during

Spider-Man's anniversary year, and I thought that was criminal.

Steve Ditko is completely at the other end of the political spectrum

from me. I wouldn't say that I was far left in terms of Communism,

but I am an anarchist, which is 180° away from Steve Ditko's

position. But I have a great deal of respect for the man, and certainly

respect for his artwork, and the fact that there's something

about his uncompromising attitude that I have a great deal of sympathy

with. It's just that the things I wouldn't compromise about

or that he wouldn't compromise about are probably very different.

Even if they have morals you don't agree with, a person with

strong moral code is a person who has a big advantage in today's

world.

CBA: You wrote in the introduction to the Watchmen Graphitti

special edition that you reached a point doing Watchmen, when you

were able to purge yourself of the nostalgia for super-hero characters,

in general, and your interest in real human beings came to fore. Do

you think that Steve Ditko's work retains substance compared

to most anything else that was produced at the time with Charlton?

Alan: I wouldn't want to claim there was any sort of deep

or great worthy philosophy in those Charlton strips; it was just that

I always have a fondness for Ditko because of his line—irrespective

of what he was drawing—and Steve Ditko didn't always draw

super-heroes. My favorite Steve Ditko work was the stuff he did for

Warren, "Collector's Edition." He was using wash and

grey tones, and that was marvelous. But yeah, Steve Ditko, whatever

he was drawing, if it was a Gorgo monster strip, or some sort of Atlas

super-hero, it was all terrific stuff.

CBA: I always had a suspicion there was an element of the

MLJ characters—The Hangman, The Shield, etc. —within Watchmen,

and upon recently reading your intro to the Graffitti Watchmen special

edition, I read that my inkling was indeed true. You were exposed

to the MLJ characters, such as The Mighty Crusaders, and so on?

Alan: Right. That was the initial idea of Watchmen—and

this is nothing like what Watchmen turned out to be—was it was

very simple: Wouldn't it be nice if I had an entire line, a universe,

a continuity, a world full of super-heroes—preferably from some

line that has been discontinued and no longer publishing—whom

I could then just treat in a different way. You have to remember this

was very soon after I'd done some similar stuff, if you like,

with Marvelman, where I'd used a pre-existing character, and

applied a grimmer, perhaps more realistic kind of world view to that

character and the milieu he existed in. So I'd just started thinking

about using the MLJ characters—the Archie super-heroes—just

because they weren't being published at that time, and for all

I knew, they might've been up for grabs. The initial concept

would've had the 1960s-'70s rather lame version of the Shield

being found dead in the harbor, and then you'd probably have

various other characters, including Jack Kirby's Private Strong,

being drafted back in, and a murder mystery unfolding. I suppose I

was just thinking, "That'd be a good way to start a comic

book: have a famous super-hero found dead." As the mystery unraveled,

we would be lead deeper and deeper into the real heart of this super-hero's

world, and show a reality that was very different to the general public

image of the super-hero. So, that was the idea.

When Dick Giordano had acquired the Charlton line, Dave Gibbons and

I were talking about doing something together. We had worked together

on a couple of stories for 2000 A. D., which we had a great deal of

fun with, and we wanted to work on something for DC. (We were amongst

that first wave of British expatriates, after Brian Bolland, Kevin

O'Neil, and I was the first writer, and we wanted to work together.

) One of the first ideas was that perhaps we should do a Challengers

of the Unknown mini-series, and somewhere I've got a rough penciled

cover for a Martian Manhunter mini-series, but I think it was the

usual thing: Other people were developing projects regarding those

characters, so DC didn't want us to use them. So, at this point,

I came up with this idea regarding the MLJ/Archie characters, and

it was the sort of idea that could be applied to any pre-existing

group of super-heroes. If it had been the Tower characters—the

T. H. U. N. D. E. R. Agents—I could've done the same thing.

The story was about super-heroes, and it didn't matter which

super-heroes it was about, as long as the characters had some kind

of emotional resonance, that people would recognize them, so it would

have the shock and surprise value when you saw what the reality of

these characters was.

So, Dick had purchased the Charlton characters for DC, and he was

looking for some way to use them, and Dave and I put forth this proposal

which originally was designed around a number of the Charlton characters.

I forget how much of the idea was in place then, but I think that

it would start with a murder, and I pretty well knew who would be

guilty of the murder, and I've got an idea of the motive, and

the basic bare-bones of the plot—all of which actually ended

up being about the least important thing about Watchmen. The most

powerful elements in the the final book was more the storytelling

and all the stuff in-between, bits of the plot. When we were just

planning to do an extreme and unusual super-hero book, we thought

the Charlton characters would provide us with a great line-up that

had a lot of emotional nostalgia, with associations and resonance

for the readership. So, that was why we put forward this proposal

for doing this new take on the Charlton characters.

CBA: So you mailed this proposal in to Dick?

Alan: Something like that, and I forget the details—it

was such a long time ago—but I remember that at some point, we

heard from Dick that yes, he liked the proposal, but he didn't

really want to use the Charlton characters, because the proposal would've

left a lot of them in bad shape, and DC couldn't have really

used them again after what we were going to do to them without detracting

from the power of what it was that we were planning.

If we had used the Charlton characters in Watchmen, after #12, even

though the Captain Atom character would've still been alive,

DC couldn't really have done a comic book about that character

without taking away from what became Watchmen. So, at first, I didn't

think we could do the book with simply characters that were made-up,

because I thought that would lose all of the emotional resonance those

characters had for the reader, which I thought was an important part

of the book. Eventually, I realized that if I wrote the substitute

characters well enough, so that they seemed familiar in certain ways,

certain aspects of them brought back a kind of generic super-hero

resonance or familiarity to the reader, then it might work.

So, we started to reshape the concept—using the Charlton characters

as the jumping-off point, because those were the ones we submitted

to Dick—and that's what the plot involved. We started to

mutate the characters, and I began to realize the changes allowed

me so much more freedom. The only idea of Captain Atom as a nuclear

super-hero—that had the shadow of the atom bomb hung around him—had

been part of the original proposal, but with Dr. Manhattan, by making

him kind of a quantum super-hero, it took it into a whole new dimension,

it wasn't just the shadow of the nuclear threat around him. The

things that we could do with Dr. Manhattan's consciousness and

the way he saw time wouldn't have been appropriate for Captain

Atom. So, it was the best decision, though it just took me a while

to realize that.

CBA: As you were writing the series itself, suddenly by #4,

you realized you had more freedom?

Alan: Oh, before #1, once I started actually writing it, I

thought, "Actually, this is sort of cool!" By the time I

was writing the first issue, I was sold on the idea. It was in preparation

when I had my doubts. But once we decided on that course of action,

and once there'd been some feedback between me and Dave, and

I was starting to see Dave's sketches and ideas, yeah, by the

time I started writing #1, I'd already gotten the characters

and they seemed solid and strong in my head. I was able to sort of

work that into the script, and it was with the very first page of

#3 when I'd realized we'd actually gotten more than we bargained

for. I suddenly thought, "Hey, I can do something here where

I've got this radiation sign being screwed on the wall on the

other side of the street, which will underline the kind of nuclear

threat; and I can have this newspaper guy just ranting, the way that

people on street corners with a lot of spare time sometimes do; and

I can have the narrative from this pirate comic that the kid's

reading; and I can have them all bouncing off each other; and I can

get this really weird thing going where things that are mentioned

in the pirate story seem to relate to images in the panel, or to what

the newsman is saying..." And that's when Watchmen took

off; that's when I realized that there was something more important

going on than just a darker take on the super-hero, which after all,

I'd done before with Marvelman.

CBA: Was one element in the genesis of Watchmen the appearance

of the Justice League in Swamp Thing, where the reader never saw the

super-heroes' faces, they never called each other by names, with

that very ominous, sinister feeling?

Alan: Like I said, Marvelman—later Miracleman—had

been my first attempt to restructure the super-hero, and to do something

that was very adult and quite strong in places. Although they admired

Marvelman, and it was obvious I could do a good super-hero-type story,

when DC first brought me over, I think the reason they gave me Swamp

Thing was probably because they might have been a little reticent

to actually turn me loose upon one of their traditional characters,

[laughter] for fear it might end up like Marvelman, with strong language

and childbirth all over the place. [laughter]

CBA: The horror! [laughs]

Alan: DC felt that, with Swamp Thing, I would work out fine,

because it was a horror strip anyway with a more adult aura around

it. When I was doing Swamp Thing, it occurred to me that, "Well,

actually Swamp Thing exists in the same universe with all these other

DC characters, so I can let that be a limitation, or something I always

steered clear of, or I could just tackle it full-on, and see if I

can stick a big, colorful super-hero group like the Justice League

into Swamp Thing, and make it work without disturbing the atmosphere

of the title." So, right, we don't show their faces very

much because I wanted the readers to think, "I know who that

is!" [laughter] We weren't letting them use their names,

just stripping all the familiar trappings away, and our intention

was to get the readers to look at super-heroes in a different way.

I was quite pleased with how that went, and it showed me, yeah, I

could take established super-heroes and write them in a way that would

not violate their essential character, and yet which would give them

a kind of freshness. But, in terms of Watchmen, where the characters

are entirely self-created, it owed more to Marvelman than to that

specific issue of Swamp Thing.

Dave Gibbon's cover art for the unrealized DC comic, Comics Cavalcade

Weekly, featuring the British artist's take on Charlton's Action Hero

Line (plus Superman!). Courtesy of the artist. ©2000 DC Comics. For

the full story on this unrealized project, be sure to check out COMIC

BOOK ARTIST #9!

Dave Gibbon's cover art for the unrealized DC comic, Comics Cavalcade

Weekly, featuring the British artist's take on Charlton's Action Hero

Line (plus Superman!). Courtesy of the artist. ©2000 DC Comics. For

the full story on this unrealized project, be sure to check out COMIC

BOOK ARTIST #9!

CBA: Just to map this out: The prototype for Rorshach was

The Question, right?

Alan: The Question was Rorschach, yep. Dr. Manhattan and Captain

Atom were obviously equivalent. Nite-Owl and the new Blue Beetle—well,

the Ted Kord Blue Beetle—were equivalent. Because there was a

pre-existing, original Blue Beetle in the Charlton cosmology, I thought

it might be nice to have an original Nite-Owl. I can't really

say that Nightshade was a big inspiration. I never thought she was

a particularly strong or interesting female character. The Silk Spectre

was just a female character because I needed to have a heroine in

there. Since we weren't doing the Charlton characters anymore,

there was no reason why I should stick with Nightshade, I could take

a different sort of super-heroine, something a bit like the Phantom

Lady, the Black Canary, generally my favorite sort of costume heroines

anyway. The Silk Spectre, in that she's the girl of the group,

sort of was the equivalent of Nightshade, but really, there's

not much connection beyond that. The Comedian was The Peacemaker,

we had a greater degree of freedom, and we decided to make him slightly

right-wing, patriotic, and we mixed in a little bit of Nick Fury into

The Peacemaker make-up, and probably a bit of the standard Captain

America patriotic hero-type. So, yeah, these characters started out

like that, to fill gaps in the story that had been left by the Charlton

heroes, but we didn't have to strictly stick to that Charlton

formula. In some places, we stuck to it more closely, and in some

places, we didn't.

Adrian Veidt was Peter Cannon, Thunderbolt; I always quite liked

Pete Morisi's Thunderbolt strip... there was something about

the art style, almost bordering on kind of Alex Toth style, though

it was never as good as Toth, but it sometimes had a pleasing sensibility

and a nice design sense about it that I was quite taken by. And I

quite like the idea of this character using the full 100% of his brain

and sort of having complete physical and mental control. Adrian Veidt

did grow directly out of the Peter Cannon, Thunderbolt character.

CBA: When I was a kid, I grew up in a rather left-wing environment,

and I remember seeing The Peacemaker with the tag-line "He loves

peace so much he's willing to fight for it." I thought,

"Ugh. Too reactionary for me," and I_passed it by.

Alan: When I first read that, I thought, "Well, that's

stupid!" [laughter] I was only about 10 or so, and I hadn't

really grown up in a left-wing family—my family voted labor,

and that was back when Labor was a socialist party—but it was

a working-class family, probably not a very well-educated one, and

so their political opinions didn't run very deep, but even so,

yeah, the idea that "He loves peace so much he's willing

to fight for it," [laughter] I could see the holes in that one

straightaway.

CBA: Keith Giffen modified the tag line to read "He loves

peace so much he's willing to kill for it." [laughs]

Alan: Bomb, murder, assassinate! Because we're not doing

The Peacemaker or The Question, we could be much more extreme with

all these characters. We probably couldn't have had The Question

living in a completely filthy slum room and being mentally disturbed,

who had a personal odor problem, and be a little guy who was ugly—you

would've had to have had Vic Sage, successful TV commentator.

I noticed, when I was a teenager, that Ditko had got some fixation

about the letter K, probably because it occurs in his own name. It's

sort of "Kafka," and "Ditko," and there seemed

to be a lot of Ditko characters with prominent Ks... Ted Kord...

Ditko seemed very fond of that sort of sound, so in some half-assed

way, that observation influenced me in giving Rorschach the name Walter

Kovacs.

With our Peacemaker character, Dave and I were saying, "This

is a guy who's a comedian," and I believe I took the name

from Graham Greene's book, The Comedians. At that point, I'd

done quite a bit of research upon various kind of CIA and intelligence

community dirty tricks, so Dave and I saw him as a kind of Gordon

Liddy character, only a much bigger, tougher guy. [laughter]

CBA: [laughs] Gordon Liddy as a "bigger, tougher guy"?

[laughter]

Alan: Sure, Gordon Liddy is a tough guy, but he's not

that huge and imposing physically. But if Liddy had comic book muscles...

and with Liddy espousing all that Nietchze philosophy, and the bullocks

of holding his hand in a candle flame and not feeling the pain, even

though it's searing. So yeah, bits of Liddy worked into The Comedian's

make-up, those sort of barking-mad, right-wing adventurists.

CBA: Are you ever going to deal with other people's characters

again?

Alan: I don't really want to, to tell the truth. Mind

you, I might change me mind, you know.

CBA: You're writing super-hero comics again.

Alan: My super-hero comics are very different, I think. After

I finished doing Watchmen, I said that I had gotten a bit tired of

super-heroes, and I didn't have the same nostalgic interest in

them, and that's still very true to a certain degree. Even if

I was actually writing for DC Comics again (and I often read Superman),

I haven't got any interest in Superman now. I'd gotten interested

in the character when I wrote it, but it wouldn't work for me

now—the characters are different, the whole world is different.

[laughs]

CBA: But you were able to purge yourself pretty quick, right?

You didn't write that many, maybe four or five Superman stories?

Alan: And that was enough. Those were ones I wanted to write,

but since then, most characters have changed so much that they no

longer feel to me like the characters I knew. So, I wouldn't

have that kind of nostalgic interest in those sort of characters anymore.

At the time, I was also saying I didn't feel that if there was

some strong political message I wanted to get over, probably super-hero

comics were not the best place to do it. If I wanted to do stuff about

the environment, that there didn't need to be a swamp monster

there, for instance. When I did Brought to Light, about the CIA activities

in World War II, that story would not have been greatly enhanced by

a guy with his underwear outside his trousers, you know. And also,

there did seem to be a rash of quite heavy, frankly depressing and

overtly pretentious super-hero comics that came out in the wake of

Watchmen, and I felt to some degree responsible for bringing in a

fairly morbid Dark Age. Perhaps I over-burdened the super-hero, made

it carry a lot more meaning than the form was ever designed for. So,

for a while, I went off to do stuff that was very non-super-hero,

and going into other areas I was interested in.

The super-heroes I'm doing now are not carrying strong political

messages, and that's intentional. They're entertainment,

and I think there are very few genres actually as entertaining as

the super-hero genre. And entertainment can be emotionally affecting

and intelligent, but I don't really want to lecture in the same

away I did when I was younger. I'm not trying to break or transcend

the boundaries of mainstream comics, because mainstream comics is

in pieces, you know?

CBA: Well, you're about the only one left standing, I

would think. [laughs]

Alan: There's no point in trying to transcend the boundaries

of something that's already shattered, you know? [laughter] The

thing to try and do is to surely try and come up with a strong form

of mainstream comics, with some occasionally transcendent elements,

but not, "Let's smash the envelope!" Perhaps I have

more of a constructive approach than deconstructive.

CBA: Is your current work on America's Best Comics, in

the wake of that "morbid Dark Age" you mentioned, a reaction

to Watchmen?

Alan: It's not so much of a reaction to Watchmen because

I've got the greatest respect for that book—it was a great

piece of work—and Dave and I did a good job there, and I'm

proud of it.

CBA: It's still in print, right?

Alan: Oh, yeah, and there's going to be a great big 15th

anniversary edition coming out next year. [laughter] I don't

know why 15th. In terms of marriages, I mean, that's like your

paper-maché anniversary or something. There is going to be

sort of a big souvenir edition, and I've got Mr. Gibbons coming

up here to little old Northampton early next week, and we're

going to do some sort of video, because they can't get me to

leave Northampton to appear at conventions, and they're gonna

see if I actually do show up on film. [laughter] We will try and film

Dave and I together.

Watchmen is a work that I've still got a great deal of fondness

for, and it was quite ground-breaking, there was a range of techniques

that Dave and I developed specifically for the book, but by the time

I finished Watchmen, they already felt like a cliché to me.

You know what I mean? I didn't want my next work to have those

same storytelling techniques, so that's why Big Numbers, Lost

Girls, and From Hell, have no captions, and no contrived, clever scene-changes.

It's just hard cuts, which felt to me like a more natural way

of doing it. I mean, I love the convolution of Watchmen—it is

a lovely Swiss watch piece, a mechanism, you know?

CBA: Wasn't it exhausting to write?

Alan: Yes, absolutely exhausting. To do something with that

level of complexity—and where the complexity's on the surface—I

thought, "Well, I never want to do this again." I have done

things that are as complex; From Hell, in its own way, is as complex

as Watchmen, but the complexities of From Hell are more in the narrative.

It's not as flashy, and I didn't want to ever have to do

anything as flashy as Watchmen again. I think that the other project

I did during the same time, The Killing Joke, suffered. Brian's

artwork is beautiful, but it's probably one of my least favorite

works in terms of my writing. It was too close to the storytelling

techniques of Watchmen, and if I'd done it two years earlier

or later—when I wasn't so much under the spell of what we

were doing in Watchmen—it would've probably been a different

and, perhaps, a better book, at least in the writing.

The ABC stuff at the moment is not a denial of Watchmen, it's

just a recognition that, hey, Watchmen was 1986, that was almost 15

years ago, and today's a completely different time. With ABC,

I want to do stories with a sense of exhilaration about them, a kind

of freshness and effervescence, a feeling that the people doing them

are loving it.

CBA: Fun!

Alan: Exactly, and I think that shows. I'm not sure how

it shows, but enthusiasm always makes the difference. The reason why

Watchmen was good was because Dave and I were loving it, doing stuff

we'd never done before, and it was really exciting. We were talking

to each other, and were charged up, and it's the same for most

of these ABC strips. In that sense, they're very similar to Watchmen,

even though they look different and read different. They're very

similar in that the level of commitment given to them and the amount

of fun we're having with them.

CBA: You're saying the ABC comics are primarily entertainment

for the sake of entertainment. Can you see returning to doing work

of more substance?

Alan: Oh, yeah! The thing is, comics is not all I do. I wrote

a novel a couple of years ago, and when I've got the time, I'm

going to do another one. I've got two or three CDs out now of

spoken-word performances, which are full of substance, with no super-heroes.

In terms of comic work, at the moment we're finishing up Lost

Girls, which I believe is a work of substance—it's a pornography,

[laughter] but it's my kind and Melinda's kind of pornography,

and I think it has meaning, social weight, and political value.

CBA: So you can have your cake and eat it, too!

Alan: Oh, absolutely! [laughter] Yeah, and with that still

going on, another CD, I've just been in the studio doing the

final mix on a CD that I think Dave Severin will be bringing out later

in the year, the guy who used to be in Siouxie and the Banshees.

CBA: Y'know, readers don't call your books "super-hero

books"; they call them "The Alan Moore books." [laughs]

That's pretty cool.

Alan: The Alan Moore books, yes, I'm happy with that.

You know, I'm hoping in the future we're going to be able

to do the stranger stuff. I'd like to do westerns and all these

old genres they used have in comics and we suddenly decided to get

rid of for some reason. I remember fondly when there used to be war

comics and western comics and teenage comics and friendly ghost comics

and things like that. Or Herbie—Herbie was one of my all-time

passions when I was growing up, and you couldn't have a character

like that in comics these days. He's too eccentric, it's

too original! So, that part of Jack B. Quick is kind of trying to

fill the hole that Herbie has left in the comics industry.

I suppose ABC comics is sort of an attempt to build an ark, where

all of my favorite concepts, things that I think should be included

in comics, you know, can maybe survive the deluge.

To make subscription and back issue orders easier for our readers (especially

those overseas), we now accept VISA and MASTERCARD on our secure

web store! ( Phone, fax,

mail and e-mail

accepted, too!)

Sign up here to receive periodic updates about what's going on in

the world of TwoMorrows Publishing.

Click here to download

our new Fall-Winter catalog (2mb PDF file)

|