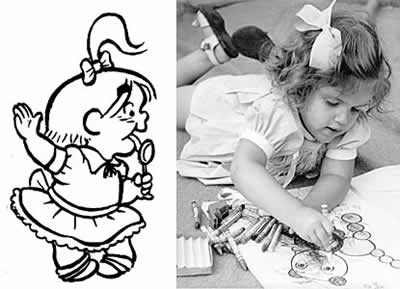

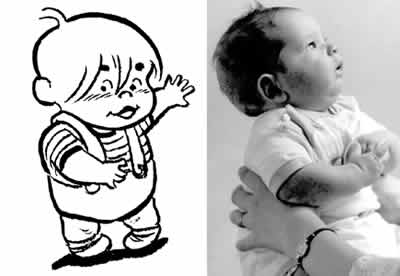

The brains of the tots (before Bernie the Brain appeared, that is),

assertive Sugar Plumm in a detail from an unpublished Sheldon Mayer

newspaper strip sample, courtesy of Robin Snyder. Art ©2000 The

Estate of Sheldon Mayer. Sugar ©2000 DC Comics. Opposite: Young

Merrily Mayer trying to keep within the lines in this 1945 picture courtesy

of the budding colorist. ©2000 Merrily Mayer Harris.

The brains of the tots (before Bernie the Brain appeared, that is),

assertive Sugar Plumm in a detail from an unpublished Sheldon Mayer

newspaper strip sample, courtesy of Robin Snyder. Art ©2000 The

Estate of Sheldon Mayer. Sugar ©2000 DC Comics. Opposite: Young

Merrily Mayer trying to keep within the lines in this 1945 picture courtesy

of the budding colorist. ©2000 Merrily Mayer Harris.

Sugar's Daddy

Talking with Merrily Mayer Harris, Shelly Mayer's

Daughter

Conducted by Bill Alger

From Comic

Book Artist #11

I originally got in touch with Sheldon Mayer's daughter,

Merrily, a few years ago through her brother Lanney, who suggested

that she might be able to help with some questions I had about their

father. I was pleased to find that Merrily is an enthusiastic admirer

of her father's work and a limitless source of information pertaining

to his life.When I began gathering material for this issue, Merrily

supplied me with copies of family momentos including a cache of previously

unpublished family photos, for which I am eternally grateful. This

interview, copyedited by Merrily, began with a series of e-mails,

was continued through the post and concluded with conversations conducted

over the phone. Thanks again to Merrily for going well beyond my expectations

in helping me to make this issue a reality.—Bill Alger

Comic Book Artist: Let's start by getting a little information

about your father's childhood. Could you tell me when and where

Sheldon was born?

Merrily Mayer: He was born on April Fool's Day in 1917

in a poor Jewish neighborhood in Harlem, New York. He was born at

home. His parents were separated at the time of birth. His mother's

name was Jennie (I'm not sure what that was short for) Grossman.

She would never tell anybody her real age, but one day let it slip

that she was 18 when my dad was born. So that would put her birth

date somewhere around 1899. My paternal grandfather's name was

Samuel Greenberger and he was a shoemaker in Lakewood, New Jersey.

My grandmother remarried (when my dad was about four years old) to

a man named Leo Mayer, and he was a meat-cutter in a butcher shop.

Leo's family was from Germany, but I'm not sure which generation

it was that came over.

My dad's father remarried, and I think dad only saw him once

or twice after that. I remember dad saying that his real father was

very special and that he thought a lot of him, but to keep peace with

his mother, dad didn't make an effort to contact him.

CBA: Was your father's last name originally Greenberger?

Merrily: I haven't been able to find his birth certificate

yet, so I don't know if he was born Grossman or Greenberger.

But I remember my dad telling me that the kids in his school teased

him for having a different last name than his mother Jennie, Mrs.

Leo Mayer. For that reason, and for the fact he had grown to love

his new father, Leo, he wanted to let Leo adopt him. At that time

not being able to afford an expensive adoption process, they just

changed his last name to Mayer.

Grandpa Leo died of cancer in around 1959, and it was after that when

my mother looked up my dad's real father, Sam Greenberger and

went to visit him in Lakewood, New Jersey. I now regret never having

gotten the chance to meet him, but when my first daughter was born

(in 1967) I got a very nice letter from him, and shortly after that

my dad called him and I got to talk (briefly) with him on the phone.

In any interviews with my dad that you might read, when he referred

to "my dad," he was talking about Leo Mayer; when he said

"my father," he meant his real father, Samuel Greenberger.

I never once heard my father refer to Grandpa Leo as his stepfather;

he chose to use the words "dad" and "father" to

make that distinction.

Shelly would acknowledge letters received for Sugar & Spike with

preprinted responses. Courtesy of Bill Alger. S&S ©2000 DC

Comics.

Shelly would acknowledge letters received for Sugar & Spike with

preprinted responses. Courtesy of Bill Alger. S&S ©2000 DC

Comics.

CBA: Was your father very talkative about his childhood? I

was wondering what his relatives were like and if they influenced

his sense of humor and his love of cartooning.

Merrily: Yes, he talked quite a bit about his childhood and

life in New York City in general. His family was quite poor when he

was growing up, so at first they thought his drawing pictures everywhere

was just a waste of time. (He did draw them everywhere—on the

back of his homework assignments, on walls—everywhere.) As I

understand it, my grandmother's (his mother Jennie's) parents

were Hungarian immigrants. Life was a struggle for them. And from

his accounts, his mother (unlike his grandmother) seemed to view everything

as an obstacle rather than a challenge. So his being different posed

a "problem" for her. I remember him telling me that when

he was quite young, people noticed his talent and urged her to enroll

him in an art school. I don't know where she found this particular

one, or whether it was part of a public high school that had an emphasis

on art for those who qualified, but she was told that his talent was

beyond what they taught there. Instead of being proud, she was furious.

"Now what do I do with you?!?" was her screaming attitude.

So no, I don't think he had a whole lot of encouragement at

that point. His mother meant well, but she was young, uneducated and

scared—viewing most things as a threat. She was a bit volatile

and would yell and scream in most instances rather than access a situation

and then clearly deal with it. His grandmother Hannah became his hiding

place, a sort of safety/comfort zone. I never got to know my real

grandfather (Sam Greenberger) very well, but for the most part the

rest of my dad's family appeared to me to be ignorant and greedy.

Did they possess any talent? None I ever noticed....

You asked me where my dad got his sharp sense of humor from and I

really had to think about that one. He really was unique and unlike

the rest of his family. His grandmother Hannah died when I was very

little and I don't remember her, but I do recall my dad telling

me of the loving and playful relationship he had with her. Maybe that's

where he got it; I'm not sure. No one else in his family seemed

to have as much going for them as he did, sense of humor or otherwise.

CBA: What comic strips did your father enjoy as a child? Did

any particularly inspire him to become a cartoonist?

Merrily: I don't remember him telling me about what he

liked to read or whom he was influenced by when he was growing up,

but he did love drawing cartoons at a very young age. Things were

tough for him growing up in New York City. Money was tight and to

his mother, any new thing was a problem that she wished she didn't

have to deal with. And the way she dealt with most situations, initially,

was to get hysterical and then yell, scream and complain. My dad had

an incredible sense of humor and found a way of making fun of the

ridiculous. So for him, it was making fun of what could have been

an uncomfortable situation and drawing cartoons became a kind of escape.

Panel detail of our favorite "midget" artist, Scribbly,

from his appearance in Scribbly #1. ©2000 DC Comics

Panel detail of our favorite "midget" artist, Scribbly,

from his appearance in Scribbly #1. ©2000 DC Comics

CBA: Did your father ever joke about being born on April First

as contributing to his sense of the absurd?

Merrily: Oh, that was sad. He didn't joke about it...

well, yeah, he did a little bit. He said things like, "I was

my mother's April Fool." But the thing that was sad—and

he never talked about it, but I know—I remember he was very sensitive,

and if you told someone it was your birthday, and it was April first,

they wouldn't believe you, and they were mean in those days.

They were so mean. I know he had a hard childhood. He did joke a little

bit about it. I think it was really sad that he was born on that day,

because he couldn't tell anybody it was his birthday... you'd

say that, and then people in those days, not only wouldn't they

believe you, but they would do something mean. I think that was kind

of sad he was born that day...

CBA: So "Happy birthday!" and then they'd be

cruel to him?

Merrily: Well, no. It was like, "It's my birthday,"

and nobody would believe him. "Yeah, sure, right, yeah, here's

an April Fool's joke for you!" And they'd do something

mean. He was really sensitive. I mean, he really thought everything

had to be so perfect and had to be a certain way. He didn't like

Archie Bunker, because he was really afraid people would believe that

was the way to think. He didn't think that show should be on

TV because people might take it seriously. He was very worried about

things, even in the comics.

CBA: Was he also influenced by animated cartoons? In 1934,

Sheldon worked as an opaquer at the Fleisher animation studio. Did

he ever consider going into animation as a career instead of drawing

comic strips?

Merrily: When I was about sixteen and we still lived in Rye

(not far from New Rochelle—about 25 miles north of New Yok City),

most of my friends were getting summer jobs as lifeguards at Rye Beach

or at one of the local beach clubs. I asked him if I could opaque

for the summer (it was about 1960) and his exact words were, "You

can opaque your life away. There's no future in it." And

that was that. So I don't know how much he appreciated having

done that, or if he just didn't want me doing it. But I do know

that for a time (and I'm not sure what year this was, or for

how long) but he did ghost animate Felix the Cat for a while. I don't

know how many people knew that because of prior contract commitments

and what not (or how much trouble I will be in for mentioning it!)

CBA: He worked on Felix the Cat?

Merrily: He did Felix the Cat and he did Mutt and Jeff when

Ham Fisher couldn't do it. He did all those things. I don't

know if he ghosted it because he was under contract or because they

didn't want anybody to know that Ham Fisher couldn't do

it. At any rate, when he did Mutt and Jeff, I liked it better than

when Ham Fisher did it!

CBA: Was this the Mutt and Jeff comic strip or the DC comic

book?

Merrily: I think it was the comic book. Yeah, and I don't

know what the deal was. My dad said something about Ham's hand

being shaky or something. Maybe Ham didn't want anyone to know

he wasn't still able to do it, he'd hurt his hand, or he

was getting older, or whatever it was, I'm not sure if he had

Parkinson's or what happened to him. I don't know how many

stories my dad did or how many issues, but he showed me one he had

drawn and it was awesome. I wish I had some of those that he did,

they were so good!

He did do fill-ins for Felix the Cat, and I can't remember for

how long, or which ones he did. But when he did something, it was

good, I mean, it was better than when the originator did it! I'd

love to see him get his hands on Rugrats... [laughter]

CBA: Do you think that DC admired him because he was responsible

for convincing the editors to publish "Superman"?

Merrily: I always got the idea from him that whenever anybody

did anything for people like that, that then you'd have to do

more the next time. In other words, if you were wonderful once, and

the next time if you weren't as wonderful, they'd get on

your case. I remember him saying things like, "The more you do,

the more you have to do!" [laughs] It's not like they'd

say, "Wow, you're great!" They'd just want more

out of you!

CBA: Your dad entered the embryonic comic book field in 1935

by working on Wheeler Nicholson's New Fun Comics. Did he ever

discuss his relationship with Wheeler and his own experiences being

a pioneer in the industry?

Merrily: I remember him telling me of instances where he got

blamed for doing things that he knew better than to do. But that the

person who had done them was afraid of being fired, and felt that

my dad, being so young (he was only 18 when he started there) would

only get yelled at, and (with the help of the culprit) could talk

his way out of it. The guy said, "I told the boss you did this

because you're not going to get fired." I remember my dad

telling me, "It was the stupidest thing. I wouldn't have

even done anything that stupid!" So then, the guy brought him

before the big boss and said, "I've already spoken to Shelly

about this and he doesn't need to be yelled at twice." (My

dad was thinking to himself, "You'd better not yell at me

once....")

CBA: In 1936, Max Gaines (who was working in a partnership

with the McClure Syndicate) hired a young Sheldon to assist him with

his burgeoning line of comic books. Did your father ever speak of

his relationship with Gaines and how they worked together?

Merrily: Yes, often. A few things stand out in my mind. I

remember him telling me about one particular incident when he was

working on a story. It was still in his typewriter and Gaines came

by my dad's desk with a huge pair of scissors, and cut Dad's

article as it was coming out of the typewriter saying, "that's

all we have room for." Snip! He cut it and made off with the

top half. He was laughing about it when he told me, but I'm sure

it frustrated him. He didn't like that. M.C. Gaines was tough

to work for. I think they had a good relationship, though. I think

M.C. really, truly loved my dad. My dad and Bill [Gaines, M.C.'s

son] were very close, also. He loved Bill. I think eventually my dad

endeared himself to people, and they really liked him.

One other thing that stands out in my mind, and might have contributed

to the fact that my dad tended to be a little superstitious. I have

a picture of a really neat (about six inches high) statue that he

carved of Max Gaines. One night while on the shelf my dad kept it

on, it just cracked and burst into pieces. I was about a year old

when this happened and my dad said I got scared and started screaming.

(I don't remember this—it was his account.) Anyway, the

next day Gaines died tragically in a boating accident. While in a

boat that another boat had crashed into, he was knocked into the water,

and being that he couldn't swim, drowned. My dad worked very

closely with Gaines, and I get the idea that he and everyone that

knew or worked with Gaines had a love/hate relationship with him.

They loved him because they had a job and hated him because he was

a pain in the neck (not the term my dad used!) to work for.

At Gaines' funeral, the rabbi was going on and on about what

a nice guy he was, and how much he would be missed. According to my

dad, this made everybody in the synagogue realize that the rabbi had

actually never met Gaines!

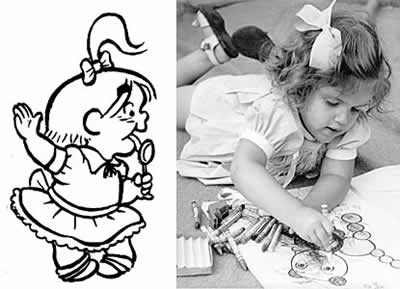

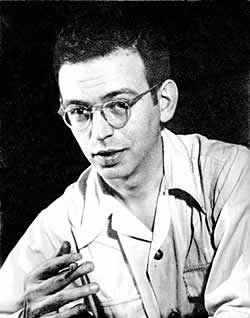

Courtesy of Merrily Mayer Harris, a studio portrait of then-DC editor

Sheldon Mayer, circa late-1940s.

Courtesy of Merrily Mayer Harris, a studio portrait of then-DC editor

Sheldon Mayer, circa late-1940s.

CBA: When your father was working at the DC/All-American offices,

he was editing Wonder Woman and All-American and he was instrumental

in the creation of a number of super-hero characters. Did he ever

discuss that with you?

Merrily: A little, but I don't remember very much about

it. He had something to do with the Green Lantern, too, and he did

talk about that. He felt that people loved super-heroes.

CBA: But he tended to concentrate on humor a little more.

Merrily: Well... he was so good at it. I don't know

which he enjoyed more. He liked super-heroes, but yeah, he loved being

funny. There was no way around that. He loved being ridiculously funny.

[laughs]

CBA: Did you father ever talk about DC's relationship

with Siegel and Shuster, who created Superman?

Merrily: If he did, I don't remember. I do remember that

he felt they should rethink their decision not to publish "Superman."

He encouraged Siegel and Shuster and helped them with the original

storyboard until it was finally accepted and ultimately published.

He helped do something that they would accept so it would get published

because he thought they really were on to something. My dad is very

good at seeing underlying things, the meta-message, and the way you

could change something and the way things could be.

CBA: Instead of pigeon-holing...

Merrily: Yeah, exactly! He never did that. He was very capable

of seeing the other side of something and what else could be developed.

He was very good at that. He was frustrated with people when they

couldn't do that.

CBA: In the mid-1930s, Sheldon created a character that he

was closely associated with: Scribbly, the boy cartoonist.

Merrily: He was Scribbly!

CBA: So Scribbly pretty much reflected your father's

personality?

Merrily: I think so. Pretty much. I read more of those than

Sugar & Spike. Mr. O'Hara, of course, was M.C. Gaines. He

didn't make him look anything like him. "O'Hara"

was an Irish guy. Not a short, bald Jewish guy, he had a lot of hair.

Maybe to make him less recognizable. But that's who it was. It

was his boss. You can look at Mr. O'Hara in a story and you can

bet that something Gaines did sparked that! [laughs]

CBA: It seems that the stories changed a lot when Scribbly

got his own comic book. It became more of a teen-age dating comic

book.

Merrily: Well, that had something to do with Leave It to Binky

and Archie and everything. They were pressuring him to make it like

those kinds of comic books. They put the screws to him to make him

do that, I think. Didn't they make Scribbly taller, like Binky,

in the end?

CBA: Yeah.

Merrily: Well, that was the Leave It to Binky stuff and he

wasn't happy with that.

CBA: Didn't he help develop Leave it to Binky?

Merrily: Maybe he did, but he didn't like doing Scribbly

that way. He'd rather have something die and leave it the way

it was than to change it and ruin it.

CBA: So he might have not been too disappointed when Scribbly

was finally cancelled?

Merrily: I'm sure he was, but he didn't want to

change it to please people and not be happy with it himself.

CBA: He later brought back Scribbly in an issue of Sugar &

Spike.

Merrily: Oh, he did? I didn't know that. I'm finding

out so much about my dad from the fans.

CBA: Yeah, Sugar and Spike were at the beach and they meet

this little baby, Scribbly Jr.

Merrily: [Excitedly] Oh, I didn't see that! What issue

was that in? [Sugar & Spike #30] Look it up! Yeah, maybe you can

make a copy for me! I'd love to read that!

That's cute, awwww... Yeah, these were family members, these

cartoons were special, and they were part of everything. That doesn't

surprise me, actually, that he would do that, connect everything.

CBA: Did he talk much about Scribbly to you?

Merrily: Yeah. Every issue that ever was, he put together

in a bound book and that was very personal to him. And later on, somebody

said, "Well, they're not valuable, because they're

in a book," but he had every one. My brother had taken that book

when he was little, and my dad was furious, and because of that, when

he died, I wanted my brother to have that book, and I told my dad

that, I said, "Give that book to Lanney, because remember when

he took it?" He said, "That's a stupid reason!"

When I said that to my brother, I said, "Take this, because I

remember when you took that because you wanted it." That's

a stupid reason for me to do it, but I gave him that book. I just

felt that should be his, but I wish I had it again. I would love to

look at it, and read it too.

CBA: Jack Liebowitz became the publisher at DC comics. Did

your father find it easy to work under him?

Merrily: I don't know how he felt about Liebowitz except

that I know he must've respected him in some way, because he

was always doing things he thought Liebowitz might like. I think it

must have been hard to work for him, because my dad was glad when

he didn't have to deal with him.

CBA: Did your dad feel the need to impress Liebowitz because

of his position at DC?

Merrily: My dad didn't go out of his way to impress people.

He had enough going for him to where, "If you like it, fine,

and if you don't, well that's your loss." I don't

think he was a brown-noser, really.

CBA: Apparently, your father got along with M.C. Gaines'

son, William Gaines, fairly well.

Merrily: Yeah, they were very close. Bill worked for my dad

when he was 14, and they were close, right to the end of my dad's

life. They loved each other. My dad really cared about him, and Bill

looked up to my dad a lot. I remember Bill when I was a little kid

and he'd come over to visit.

CBA: What did he do for your father at DC/All-American?

Merrily: He was about 14. Max used to bring him to work, so

my dad would keep him busy. It was just give him something to do.

Put him to work. He was only about five years younger than my dad,

but that's a big gap between 14 and 19. He said Bill used to

be mischievous. My dad would have to work and watch him at the same

time. [laughter] I'm not sure what he did for him, but it was

my dad's job to keep him out of trouble. [laughs]

CBA: What did you think of him?

Merrily: When I knew him, he was nothing like the way you'd

see him later on TV. He was very quiet. When he was in my dad's

house, he always acted like he was a little kid. Like he was being

watched and supervised. We weren't little kids together...

believe it or not, he was almost my dad's age! I was a little

kid! But around me—I was around six or seven—he always acted

like he was one of the little kids. He always sat there as if he was

going to get into trouble, like he was in the principal's office.

It was really weird. [laughter] And he didn't have the beard

or the long hair or anything. He was in a suit and tie; he'd

bring different girls up for my dad to approve of or disapprove of.

CBA: In the 1950s, Bill Gaines had troubles with the congressional

committee investigating the influence of comic books on juvenile delinquency.

Did your father ever comment on Bill's role in the proceedings?

Merrily: Yeah, I don't remember the whole thing. But

I remember when Mad magazine was a comic book and there was a cover

with a guy's head cut off. It was a head lifted way up high and

you could see the cuts where it was cut off. I remember we had a copy

of that—my dad had it. I remember we were late to school one

day because it was on the news that they were coming down on Bill

Gaines. He loved Bill dearly, and he never said anything against him,

ever. They were very, very close, right up to the end of my dad's

life. Bill did a lot for my dad. There isn't anything that either

one of them wouldn't do for each other. But I remember the comment

my dad made, "That was unfortunate," He might have been

referring to the decision Bill made to do that material, or that the

congressmen felt that way about Bill. I'm not sure what the "that"

was. I was ten. I was very young. I remember when Mad came out as

a magazine, how incredibly funny it was. I think my dad was kind of

happy with it, and relieved that Bill found a medium and a way to

do what he was good at that was acceptable, that people liked it and

he was doing well with it.

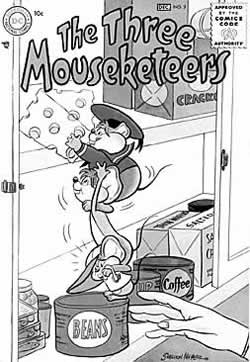

While Shelly first developed his rodent trio back in 1944 as a strip

in Funny Stuff, his "Three Mouseketeers" didn't receive

their own title until 1956. Here's the cover to #5. ©2000

DC Comics.

While Shelly first developed his rodent trio back in 1944 as a strip

in Funny Stuff, his "Three Mouseketeers" didn't receive

their own title until 1956. Here's the cover to #5. ©2000

DC Comics.

CBA: Did your father ever comment on Mad magazine?

Merrily: He thought it was a very funny magazine. The comic,

I don't know what he thought of, but the magazine he thought

was very funny. He liked Don Martin and Ernie Kovacs.

CBA: In 1948, your father stepped down as editor at DC so

he could concentrate on writing and drawing. Did he discuss this decision

with you?

Merrily: Yeah, it was a headache. He just really wanted...

he loved to draw, and he just didn't want to baby-sit anymore.

[laughs] He didn't put it that way, but that's what I got,

he just had enough of the hassle, he just wanted to draw pictures.

That's what he really wanted to do, he wanted to get out of the

city, be in the country. He loved horses and trees and didn't

want us raised in the city. So he left to draw pictures, because that's

what he really loved doing. He said he could draw pictures for the

rest of his life. He liked writing stories and stuff and seeing them

printed, but he didn't really like the editing deadlines. It

really squeezed him. He didn't like that. He just wanted to draw

pictures. That was so much fun for him. He could do that under a deadline—"Draw

me five fat guys!" He could nail them. "With big ears!"

He could do that in a heartbeat, no problem.

I just get the idea he was very relieved when he was in our house,

writing. He liked that so much to go into his studio and look out

at the trees and write. He loved that. He did not like the rat race

of New York City. He loved the work, but one day he said to me, "I'm

going to call the office, I want you to listen to this. I want you

to listen to the stupid things I have to deal with." [laughter]

So he gets on his speakerphone. These guys at DC are in a conference,

and I couldn't believe it! It was like... he pulled everything

together. He made everything work. He really did. He was a great organizer

and a good leader, and he got tired of having to do that. "I

don't want to lead everyone by the nose anymore! They can do

what they want." He did care what people thought, but he just

got tired of how ridiculous the bureaucracy was. He cared about the

whole picture. A lot of people didn't in those days, there were

a lot of people that were running scared, that were stymied by being

yelled at their whole lives, that they couldn't see the forest

for the trees.

CBA: Was there anything in particular that bothered him about

his editing job at DC?

Merrily: Well... I'm sure there was. I just have to

pull it out of my brain. [laughs] I know there was, because I can

remember he'd come in laughing... he'd tell me things

he had to deal with. I'm glad he laughed about the stuff, because

he was under quite a bit of pressure. My mom didn't hear well

and he kind of got frustrated telling her things. She'd sit there

with the same look on her face and he lived for feedback! He'd

always get a rise out of me, because I'd say something. So he'd

tell me. My mom was very quiet. They really were very different.

CBA: Irwin Hasen seems to think that your father made a big

mistake by not continuing with his career as an editor.

Merrily: Well, a lot of people felt that my dad made big mistakes

by not going to Hollywood, not doing this, not doing that. He didn't

make a big mistake. He did exactly what he wanted to do! He wanted

to get out of there! He wanted to get out of New York City! He wanted

to get out of that office! He wanted to be by himself! He wanted to

draw cartoons and there was no mistake to it! I don't think he

had any regrets about it! He never felt, "I wish I made more

money, I wish I did this, I wish I did that." He did exactly

what he wanted to do! He moved into our house, and built a swimming

pool. He had friends over, and we went swimming, had pool parties,

and Fourth of July barbecues. He drew pictures. People liked him and

respected him, and he was very, very happy with that! He really was.

He never said to me that he'd made a mistake, I never heard him

say, "I wish I hadn't done that." I mean, really never

heard him say that as far as the career move.

CBA: Did your dad have one character he created that was his

favorite?

Merrily: I don't know. I think whatever he was working

on at the time. He was very sad when The Three Mousketeers got cut.

It was his choice, I think, that Sugar & Spike took off, so he

had to concentrate on that. I remember him coming in and saying, "Well,

no more Mousketeers," to my mother. He was kind of sad about

that. Whatever he worked on, he loved working on it. It would be easier

to tell you what he didn't like, which I don't even know.

[laughter] He enjoyed drawing anything. He would be drawing, and he'd

be talking to me while he'd be drawing. I'd be telling him

something about school, and he'd be drawing a little caricature

of the situation, and then while I was still talking, he'd show

me what he drew. He loved to draw anything. I know he didn't

consider that a chore, he loved Halloween, he loved everything.

CBA: After your father gave up The Three Mousketeers, another

artist continued it.

Merrily: Well, he didn't want that to happen. He wanted

to do it, but they wanted him to concentrate on Sugar & Spike,

and... now, what's the name of that guy? I've met him,

he was heavy-set, what was his name? Who did The Mouseketeers afterwards...

Rube...?

CBA: Grossman?

Merrily: Yeah, Grossman! Rube was very sweet, dad liked him,

but he didn't like the way Rube did The Three Mousketeers, and

it died after that! I remember him saying, "They killed it!"

[laughter] It wasn't good anymore, and he was sad about that.

CBA: Was he still writing it?

Merrily: No, he totally abandoned it, as far as I know, because

he had to do Sugar & Spike. He loved The Three Mouseketeers and

he liked Rube. Rube came to our house a few times, but dad realized

the guy was limited.

CBA: Did other people from the comics industry visit your

family?

Merrily: Not very many. Bill Gaines was one who came a lot

and every once in a while Rube Grossman. The only socializing my dad

did at our house was when he took a writing class, and he invited

classmates to come over with their wives every Fourth of July and

we'd have a party. Oh, Irwin Hasen, yeah, he visited a little.

My dad needed space to be creative, and he didn't surround himself

with a lot of people. He loved creative people and loved spending

time with them, but he didn't have them over too much because

a lot of them were very neurotic. He had trouble dealing with neurotic

people. [laughter] No, he really did. He didn't forgive people

for a whole lot of stuff... he was very critical. Not critical

to them, but he'd just never have them back! [laughs]

CBA: So you knew Irwin Hasen?

Merrily: Oh, yeah, I knew him very well. My dad was pretty

close with Irwin. Irwin came to the house a lot. He was about four

feet tall, a little younger than my dad maybe, and he used to date

these girls who were 18 and eight feet tall! [laughter] My dad would

call them "Mutt and Jeff." [laughs]

CBA: Was your dad pretty excited about Sugar & Spike being

a hit?

Merrily: Oh, he was proud. Yeah, he was. He seemed to enjoy

The Mouseketeers a little bit more, now that I think of it. He really

got into that. But he was happy doing Sugar & Spike, and he was

very proud that it was a hit. He enjoyed being the celebrity when

my friends came over and talked to him. He loved that.

CBA: Before Sugar & Spike was published, did your father

tell you he was working on a comic book based upon you and your brother?

Merrily: No, I don't remember that he did. All of a sudden,

it just appeared on his drawing board, and he was telling me about

it, and he was very proud of it. "What do you think? Isn't

this cute? What do you think of this? What do you think of that?"

And for some reason, I didn't like being in the studio, because

I always got yelled at. I'd touch something and tick him off

somehow, so I really didn't want to be in there, and so I said,

"Yeah, that's great, dad," [laughter] and I'd

leave. If you turned around and breathed on something, you never knew

what you were going to get yelled at, and I just didn't really

want to be in there.

He really didn't say anything about the comic being based on

us. But I did get the idea it was about us, even though it was called

Sugar & Spike, and I remember being really offended that our names

weren't in it, I would've been much more thrilled if our

names had been in it. He never called me "Sugar" and that's

probably why I wasn't thrilled.

I was impressed by his concepts about babies—even though it

was just a comic book. I'm sure when any psychologist or anybody

else reads it they would have to admit that he had insight into how

children act. I remember people saying, "Oh, he doesn't

know what he's talking about!" But now they realize that

he did. He was self-educated. He didn't go to graduate school

for psychology or anything. He figured it out on his own. A lot of

things about babies' early communication that took psychologists

a while to figure out. I'm sure people benefited from it. I know

I did. Besides, they're funny!

Courtesy of Steve Cohen, the original cover art to S&S #94, featuring

the debut of Raymond, the series' first African-American co-star.

©2000 DC Comics.

Courtesy of Steve Cohen, the original cover art to S&S #94, featuring

the debut of Raymond, the series' first African-American co-star.

©2000 DC Comics.

CBA: Your father said in an interview that he was asked by

DC to compete with the rash of Dennis the Menace imitations that were

flooding the market. "I resisted all suggestions that it be another

Dennis imitation. I remember saying, 'When Ketcham dreamed up

Dennis, he looked around him and found what he was looking for in

his own kid. To that degree only, I will imitate Ketcham... I too

will look around me and see what I come up with.'" Do you

know if he considered Dennis to be much of an influence on Sugar &

Spike?

Merrily: That's the first I've heard of him saying

anything about it. I don't know that he was influenced by Dennis.

If DC asked him to do something similar to Dennis the Menace, maybe

since Ketcham looked at his kids, then my dad looked at his own, because

looking at movies of my brother and I before we could talk is how

Sugar & Spike came about.

CBA: Yeah, he said that... "My kids were already entering

their teens so I had to look elsewhere." He said he couldn't

come up with any ideas until he took a look at the home movie....

Merrily: The movies of us, yeah, I have those!

CBA: Did he discuss watching you and Lanney in the home movie

and coming up with the concept for Sugar & Spike?

Merrily: Yes, and this is the first I've heard that it

had something to do with Dennis the Menace. I remember I had a Dennis

the Menace doll, and he didn't really like it. [laughter] I wanted

one and he didn't want me to buy one, so I remember that. There

was a little rubber doll. It wasn't that cute and it didn't

look like Dennis the Menace really. So one day on my birthday, I came

home and there was one hanging from the mailbox. It was in a box and

I opened it up and I said, "Oh wow, a Dennis the Menace doll!

Where did it come from?" My mom said, "I don't know.

Someone hung it on the mailbox." I was so pissed because I thought,

"My God! If I'd stayed home, I would've known who gave

me this!" I was so sad and my mom took me in my room and shut

the door. She said, "I gave it to you. Be quiet. I just didn't

want dad to know." [laughter] "Don't say anything!"

So I could never tell my dad where that stupid doll came from. I don't

know if he didn't like Dennis the Menace because he didn't

want to be reminded of how he was asked to imitate something. I don't

know. But I do remember he didn't like that doll and didn't

want me to have it. [laughs]

CBA: I noticed Spike has overalls, like Dennis.

Merrily: Well, I'll tell you right now, my dad did not

like to imitate things. He considered that stealing. If he saw something

cute, he'd draw it. Maybe he was forced to do something like

that when he came up with Sugar & Spike. As cute as Dennis the

Menace was, Sugar & Spike was nothing like it, really.

If Spike looked like Dennis the Menace, it was either because he was

asked to do that. Or because my brother had overalls that looked like

that, that were always unbuttoned and falling apart. Those clothes

that Sugar and Spike have on are drawings of the way we were pretty

much dressed. Yeah, my slip was always showing, and my brother wore

overalls (and I did, too).

CBA: Did you wear a ribbon and have blonde hair like Sugar?

Merrily: Yes, my mother always put a ribbon in my hair. It

was very important in those days to put ribbons in little girls'

hair. My hair was never messy like that. I did not look like Sugar

that way. My hair was always braided neatly, but it was very blonde.

You'll see that in the pictures, they're black-&-white,

but you can see how blonde my hair was.

CBA: And Lanney's hair was red like Spike's?

Merrily: His hair was a little darker. It was very light brown—dark

blonde... dishwater blonde. It wasn't red. My mother had red

hair and maybe he made Spike's hair red so he wouldn't look

like Dennis. I really don't know.

CBA: Sugar and Spike were often consigned to sitting in the

corner as punishment. I'm assuming that this is something you

and Lanney also experienced?

Merrily: I don't remember ever having to sit in the corner,

or stand in the corner, I don't know where that came from. I

think some of the people that we babysat for did that. I don't

remember, I don't know where that came from. My parents didn't

do that. They were very creative with their punishment, and they were

very careful. Dad didn't want to ruin us, and he was very careful

of what he did and didn't do. They were very into progressive

education for children, and letting them be autonomous. Although he

didn't really allow us to be autonomous, he thought we should

be. [laughs] So he was careful not to... he didn't want to

damage us like that, so he never did that. And he didn't smack

our hands when we did something wrong, either. He would yell and scream

a lot, you'd have to listen to him for an hour-and-a-half. [laughter]

CBA: Were the characters' personalities at all based

on your own?

Merrily: Oh, very much, yeah. I was older than my brother,

and I was an instigator. [laughter] I was Sugar and my brother was

the one who was always getting into trouble for everything I did.

In those days it was unusual for the woman to be the leader. But what

you have to understand is, I was older. So, naturally, the younger

kid followed the older kid.

I remember thinking my brother was very stupid, and that's very

sad that I felt that when I was little. I remember my mother said,

"He adored you! He just thought you were wonderful!" I was

looking at one picture of my brother where he looked at me like that,

and I was looking at him like, "You piece of garbage!" [laughter]

That's so sad. Well, because he was a little kid, and he got

into things! My parents set us up for that, too, not to get along.

I mean, they did! "Ah, he's being stupid, don't..."

they separated us, they totally separated us. We weren't allowed

to do anything together. My dad had bought my brother a typewriter,

and mine hadn't come yet. We were grown up, in high school, and

I had typing homework. My brother said I could use his typewriter

to do my homework, and my dad wouldn't let me use it! He wanted

to buy me my own, and we both thought that was ridiculous. He said,

"Well, my brother used to break everything of mine, so you're

going to have your own." Well, his brother was 11 years younger

than him, and we weren't [11 years apart in age]. He had issues;

my dad definitely had issues.

Then, later on, when we grew up, he would base it on the neighbors'

kids. There was a kid across the street he'd put in. Anyone he

saw. He'd wander around the neighborhood, watching things kids

did, and write about that. [laughter] He was afraid to get things

from the TV. He didn't want to steal things. Then he wanted me

to bring my daughter around because he wanted to write about her.

And then later on Sugar became some of the things that our neighbors

and the people that my friends babysat for did. I don't know

why he stopped doing Sugar & Spike. I never did find that out.

I don't know if he was running out of things to do, because all

the kids around him were growing up, or if DC decided to stop the

whole thing.

CBA: Well, from what I understand, his eyes were failing.

Merrily: Yeah. That's true, too. Yeah, they were doing

very badly, but he didn't stop drawing for a living. So that

couldn't have been it.

CBA: Supposedly, that's the main reason he stopped drawing

Sugar & Spike, but I wonder if sales were falling in the early

'70s.

Merrily: That sounds closer to the real reason because he

never stopped drawing, he drew right up until the last day of his

life. He drew constantly. He drew when he was on the phone. You know

how people draw little circles and doodles? He would do funny _stuff,

constantly! He drew right up to the end. But yeah, his eyes were failing.

Cecil—a.k.a. Spike—himself. From a sketch by Sheldon Mayer.

Art ©2000 The Estate of Sheldon Mayer. Spike ©2000 DC Comics.

Opposite: Merrily Mayer's brother Lanney as infant in a 1945 picture

courtesy of his older sister. ©2000 Merrily Mayer Harris.

Cecil—a.k.a. Spike—himself. From a sketch by Sheldon Mayer.

Art ©2000 The Estate of Sheldon Mayer. Spike ©2000 DC Comics.

Opposite: Merrily Mayer's brother Lanney as infant in a 1945 picture

courtesy of his older sister. ©2000 Merrily Mayer Harris.

CBA: I thought that for a short while in the 1970s he couldn't

see well enough to continue drawing.

Merrily: He had cataracts and in those days, they took the

whole lens out. He never could see well after that. They took the

lens out and they gave him these thick glasses. Now... I was almost

blind, too, but they put a lens in my eye. They didn't do that

for him. Now they do an inter-ocular lens. I'm now an android

[laughter], but they didn't do that for him. I remember he had

these really thick glasses after the operation. He couldn't see

very well, but he did draw stuff.

CBA: Was he disappointed when Sugar & Spike was cancelled?

Merrily: I don't remember, but when his eyes went, he

wasn't happy. And he was practicing. He'd shut his eyes

and practiced drawing in case he went blind. He would draw with his

eyes shut. And he'd draw these incredible things with his eyes

closed! [laughter] He said, "It only works if I don't take

my pencil off the paper." So, he was practicing. He was ready

to go blind and he wanted to make sure he could still draw.

CBA: I read that he was starting to go blind so he stopped

drawing Sugar & Spike. Then a year or two later, he had the operation

and started drawing comics again.

Merrily: But it made it hard, though. He could never really

see well the way they did his eyes. He had a very hard time after

that.

CBA: It has been reported that your father didn't want

anyone else working on Sugar & Spike. Did he ever mention this

to you?

Merrily: I don't know. I never heard that. But if someone

told me that, I would believe it, because The Three Mouseketeers book

was killed when he wasn't on it. I mean, it didn't do well.

I know he would get very upset at the way they would ink things and

the colors they would choose. "Those idiots!" [laughs]

I do believe that. Because the Sugar & Spike book was his baby

and I don't think he wanted it bastardized. I mean, he really

loved it and wanted it done right—the way he thought it should

be. And he didn't think anyone else could do it. When it was

done, it was done. He didn't want it to die because it wasn't

as good. If he had to stop, that would be that.

CBA: Did you read Sugar & Spike when each issue came out?

Merrily: I did. Not religiously. Not every single one, but

I read some of it, because he'd ask me to, and it was very cute.

My dad and I didn't really become friends until, I don't

know, very recently, actually... maybe within two or three years

before his death. After I started college he had an easier time relating

to me as an adult. I was studying history and asked him questions

and he could answer all of them. He was a history buff, so he appreciated

the classes I was taking. Then, we had something in common, and prior

to that, we didn't. I mean, we didn't like the same kind

of music, didn't have anything in common, really, except that

we were related! So when I started studying history, we talked about

it. When I told him something he already knew, he was very impressed,

"Oh, wow, you know that?" [laughs] That was the basis for

our friendship. I apologized for calling him one day, I was doing

a paper and needed to know something, and called him up and said,

"I'm really sorry," because I remembered how he was

about his time being invaded, and he said, "No, that's fine!

Whenever you have a question about history, you should call me up

and ask me. As a matter of fact, tell your whole class they should

call me, too!" [laughs] Not that they really could, but they

probably needed to... [laughs] If you want the truth, call Sheldon

Mayer! [laughs]

CBA: What did your friends think of your dad's occupation?

Merrily: There were three of my very good friends in high

school who were big fans of S&S and collected all the issues.

I remember one day when I was walking home from school seeing a friend

of mine walking away from the street I lived on. She didn't live

anywhere near our house. I at first thought she came to visit me and

was leaving because I wasn't home. I invited her back. She informed

me that she had interviewed my dad for the school newspaper and was

finished and was now leaving. That was someone I, at the time, considered

to be one of my very closest friends, but now, had completely no interest

in spending time with me. She came to see my dad, saw him, and left.

I was proud, but at the same time crushed. That happened more often

as I got older. There'd be guys I had gone out with for a period

of time that when we, for whatever the reason, stopped seeing each

other, would still come over and had a similar disinterest in seeing

me. They just wanted to "hang" with my dad.

CBA: How did he deal with his fans when they contacted him?

Merrily: He loved it! He paid somebody—this kid named

Chris Wood to answer his fan mail. My dad told him to let him know

if somebody wanted to meet him or had anything really interesting

to say. So he'd answer those. He would also dedicate stories

to people. Sometimes he'd write back or call them. If they wanted

to meet him, and they seemed interesting, he would meet them.

CBA: Did fans ever come by the house?

Merrily: Not people he didn't already know. He'd

go into town and meet somewhere (no matter where they lived). He had

one I'll never forget: Nell Rose Cottal, a girl he drove to see

with her mother and brother. They met and had lunch together. They

didn't come to the house. He'd go visit them. He talked

about her a lot. He loved the fact that she loved his work.

CBA: Did many things that happened to you in real life find

their way into your father's stories?

Merrily: I do remember one particular day (I must have been

about 14) when a friend of mine was telling my dad about a little

girl she had babysat for. The little girl was about a year-and-a-half

old and when she had done something wrong, her mother would slap her

hand. This one day she made a mistake and then went to her mother

with her hand out for her to smack. I remember my dad having been

very touched by that, and in at least one issue, he had Sugar do that.

I remember the incident that sparked my Dad to do the cover for Sugar

& Spike #4. My brother had gotten into the jelly (he was about

four or five) and got some on his face and hands. My mother was a

little annoyed at him, and he said, "How'd you know it was

me, you weren't even in the room? Do you have eyes in the back

of your head?" (My mother was just ticked off because he had

gotten jelly everywhere, and then was rude about it.) My dad, in his

true comedic form, just put it into his next issue.

CBA: Did you know Whitney Ellsworth?

Merrily: I never met him. I think my dad did, though. He used

to call him "Whit."

CBA: He was a long-time editor of a lot of Sheldon's

books, including the early Sugar & Spikes.

Merrily: Oh, really? I didn't know that. I saw his name

as something to do with the Superman show on TV in the '50s.

I watched that, and I remember Whit Ellsworth's name was on there,

but I didn't know in what capacity he, if at all, worked with

my dad.

CBA: Did he ever mention having any troubles with the editors

on his books?

Merrily: No, the only thing he ever complained about was the

colorists. He often didn't like the way it was colored after

he sent it in. "Those idiots, they didn't make this contrast

enough!" He never complained about anything else, the writing

or the editors, anything as much as the person who did the coloring.

If something covered up one of his details, that'd upset him.

He did his own inking, so he wouldn't have to worry about that,

but the coloring was done after he sent it in.

CBA: I've noticed that on a lot of his original art he'd

put detailed instructions for the colorist.

Merrily: Oh, yes! Absolutely! He did that, because it was

very important to him. He felt these guys just went in, did their

job, got paid and went home. He was a stickler for detail. It meant

something to him. When you color over something, you lose some of

the detail. Like, if you're going to have spaghetti on a plate

and on a tablecloth and the spaghetti was red. You wouldn't have

a red plate and a red tablecloth, because they wouldn't know

what it was. They would do stupid things like that, and it would upset

him. [laughter] That's the kind of thing that would bother him

that they wouldn't notice.

Shelly's cover art for the 1971 aborted Sugar & Spike Pocket

Treasury. Art ©2000 the Estate of Sheldon Mayer. Characters ©2000

DC Comics.

Shelly's cover art for the 1971 aborted Sugar & Spike Pocket

Treasury. Art ©2000 the Estate of Sheldon Mayer. Characters ©2000

DC Comics.

CBA: I guess you never crawled through a fence to get to a

neighbor's yard like Sugar and Spike were always doing?

Merrily: Oh, we had a fence. I don't remember being able

to go over or under it. [laughs] They were picket fences like that.

I think dogs used to climb through and get away. And so he had the

kids doing that... Oh, wait a minute! I know where that came from!

Yes, I do! I think once he put the playpen upside-down on my brother

when he was getting into something for a minute so he wouldn't

get hurt, and then I went and lifted it up and let him out. That's

where that came from. We used to help each other escape from the playpen.

[laughter] A lot of what would be the fence was the playpen. I would

always help him escape. We used to do that. [laughter]

CBA: Your father put together a short Sugar & Spike animated

cartoon. Was this in color or black-&-white?

Merrily: It was in color, but it didn't do justice to

his talent. I don't know when he did it. It was just something

he tried to do. The cels didn't match. The arms didn't match

the rest of the body on one particular character and there were other

problems like that.

CBA: What did you think about Rugrats?

Merrily: I was sort of offended by them, really. I thought

it was a swipe of Sugar & Spike. I would love for one of them

to say, "Yeah, I love Sugar & Spike and I wanted to put it

in a cartoon." I'd love for someone to admit to me they

were totally influenced by Sugar & Spike. It's cute but the

drawings are kind of grotesque. Tommy is a very sweet, loving, cute

kid and they're nice kids and the stories are pretty much like

Sugar & Spike in some ways. Along with the whole premise of "Those

grown-ups don't understand us," only babies understand other

babies. I just think they could be cuter. I really don't like

Hey, Arnold! and all of those ugly cartoons. It really bothers me.

My father worked very hard to make his look appealing.

I'm sure Sugar & Spike inspired Rugrats and I'd love

for somebody to say that! They waited until he died, and then they

did it, it seems to me. I think somebody should give him credit for

having introduced the concept that babies have their own language.

CBA: Do you think your father would have liked Rugrats?

Merrily: He wouldn't have liked it. He called that limited

animation. But then again, there's a whole new way of thinking

in cartoons. I think it started with Sesame Street. Those puppets

were kind of weird looking. And maybe that's a way of not having

everything be pretty and cute. I love The Simpsons, though. I find

it terribly funny. I was sort of taken aback at the way they looked

at first, too. So maybe that's just a new thing that I'm

too old to appreciate. You can't get uglier than Homer Simpson.

But the show is riotously funny. It's a really hip cartoon.

CBA: Do you have a favorite character that your father created?

Merrily: I don't have a favorite character he did, but

there are certain things that he drew that were so funny. He'd

do a caricature of somebody that did something silly, and that's

what I loved. When we were going somewhere and he would depict something

stupid that happened, put it on paper and make you laugh. Those were

my favorite things he did. His stories of Sugar & Spike were very,

very cute, and I loved all of them, but my favorite things were when

he'd make fun of life on paper, and then just hand it to me.

[laughs]

To make subscription and back issue orders easier for our readers (especially

those overseas), we now accept VISA and MASTERCARD on our secure

web store! ( Phone, fax,

mail and e-mail

accepted, too!)

Sign up here to receive periodic updates about what's going on in

the world of TwoMorrows Publishing.

Click here to download

our new Fall-Winter catalog (2mb PDF file)

|